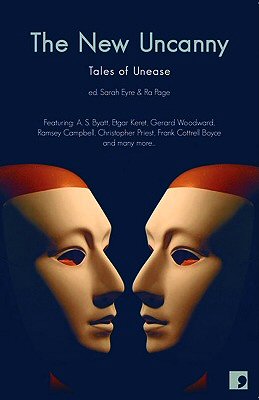

I am currently teaching an online horror literature course in “Psychos and the Psyche” for graduate students in our MFA in Writing Popular Fiction program at Seton Hill University. This month we are studying Freud’s article on “Das Unheimlich” and reading a fascinating new anthology of horror fiction called The New Uncanny: Tales of Unease, edited by Sarah Eyre and Rah Page (Comma Press, 2008). The book features some of the best British horror authors alive, including Ramsey Campbell, Nicholas Royle, A.S. Byatt, Christopher Priest and many more…even Matthew Holness (whose double, Garth Merenghi, is echoed here). The book definitely deserved the 2008 Shirley Jackson Award for “Best Anthology” for its ambition, and it makes for an interesting study in all things Unheimlich.

The book, essentially, is a literary experiment. All its contributors were challenged to read Freud’s seminal essay on “The Uncanny,” and then write a fresh fictional interpretation in order to explore what the Uncanny might mean 100 years later — today — in the 21st century, “to update Freud’s famous checklist of what gives us the creeps.”

The introduction by Ra Page is an excellent survey of “The Uncanny” in its own right, discussing how Freud provided a “literary template…a shopping list of shivers” that horror writers have managed to return to again and again over the past century. Page explains Freud’s essay in one of the most clear and careful ways I’ve ever seen in print. When discussing the tales in The New Uncanny, Page notes that the majority of the stories feature either the double or the doll most often, and turns to another essay on the Uncanny — Rilke’s “Dolls: On the Waxwork Dolls of Lotte Pritzel” (1913) — to discover convincing reasons why. I love the way Page concludes the introduction: “[The Uncanny] puts us on edge — that place we really should be from time to time — and reminds us: it’s us that’s alive.”

Keeping with the experimental spirit of this book, I thought I’d ask my “Psychos and the Psyche” class to review the book as a group. I have assigned each classmate a specific story in the book, and asked them to write a response (in a comment to this blog entry) that addresses the following three questions:

1) How does the author try to “update” the Freudian Uncanny in this story?

2) Does the story succeed as a work of uncanny literature?

3) What does the story teach us about the Uncanny in today’s culture?

[Warning: spoilers are inevitable! SURPRISES WILL LIKELY BE GIVEN AWAY. And all rights and opinions belong to the commenting students themselves. They will appear intermittently between now and the deadline of Oct 6th.]

Update: You can read MY review of this book (with fewer spoilers) on The Goreletter here: “A Double-Take on The New Uncanny” — MAA

You can order The New Uncanny directly from Comma Press online (be careful to note the different options for overseas orders).

This is one of the reasons I always find it so profitable to check out your blog, Mike: because you have this knack for introducing me to new books that I simply have to read. THE NEW UNCANNY sounds uncannily fascinating.

I hope the online class is a success.

The Dummy

“The Dummy” is a short story found in the anthology The New Uncanny. The premise of this anthology was to find out what modern authors felt was uncanny by today’s standards. They used Freud’s treatise on the subject as their jumping off point. The short story “The Dummy” takes into account what Freud called an inanimate object either being considered alive or in actuality and unknown to the main character, being alive.

In the case of this story, a traffic dummy, which serves to warn drivers about construction on a highway in Belgium, is the uncanny subject. The story contains e narration of this dummy’s point of view. In Victorian and Edwardian times when Freud would have formulated and written his treatise, this particular dummy would be considered an automaton. By today’s standards moving dummies aren’t too uncommon. Mannequins in stores move, and holiday displays often feature moving Santa’s and elves. So the story serves at trying to update the idea by making this a robotic flagger at a construction site the uncanny object of the story. The second narrator of the story is the human character. He admits that he has never seen a dummy like this. He sees it as so human that he mistakes it for a man lying in the road when he comes upon the dummy again. The dummy at one point even seems to have a pulse and heart beat. This takes into account the Freudian idea of the uncanny that a dummy may be alive without human knowledge.

What the story attempts to do is make us feel like the mannequins and dummies of the world are watching us and commenting on our every move. It attempts to play on the modern paranoia that we are never alone by making even the human-like dummies of the world watching us. The strange thing is police forces started using this idea in the 1990’s. They park a cruiser in the median of a busy highway with a mannequin dressed in a deputy’s uniform in it. This causes drivers to slow down and be more cautious because they think a police officer is there. The problem with this story is the unnerving sense of dread it tries to instill isn’t there. Part of the uncanny according to Freud is the sense of unease we get from the object of the uncanny. In the case of “The Dummy”, we are supposed to be unnerved that this road mannequin is commenting and watching the narrator’s every move. The author, however, gave the narrator a more unnerving story than the dummy watching us. We find out that the narrator is a bit on the edge of sociopathic intent. He plans on killing his children. The dummy makes a vague comment on this like he has seen it before, but still the unease comes from fact that the narrator plans of killing his children and has kidnapped them, not that the dummy is commenting on this. In that way, “The Dummy” fails to bring the unease of the uncanny to play.

The Underhouse, even in its title, plays with several of the themes Freud tried to develop in his essay. A house underneath is one that is hidden, unhomelike, possibly dangerous. A cellar is often a place, due to darkness, bugs, moisture, fungus, mold, etc., which people, especially children, fear. Yet Woodward manages to twist a relatively straightforward play on words in several ways in six short pages. He includes the themes of doubling, repetititions, and confusing reality and imagination in rather unique ways.

As the story begins, it almost sounds like a prologue, an author explaining him- or herself before getting into the story proper. It explains the narrator’s fascination with the unusual or uncanny perspective even as a young child. As a presumably grown man, upon investigating his house, he realizes that his cellar is a near-replica in size of his livingroom. So starting with the fearful place, he uses doubling and repetition to completely recreate his livingroom inversely to gravity. That is, he uses the ceiling of the cellar as the floor of his replica mirror-image of the room above. The story reviews the difficulty in finding every exact piece of furnishing as well as duplicating it in defiance of gravity to look exactly as the livingroom does.

The reader wonders why he is doing this, beyond his fascination with the mirrored perspective. In another twist, it becomes clear. The narrator finds he must share this unusual perspective with others. So he purposefully seeks out vulnerable people (homeless or near-homeless, drunk or otherwise impaired) and plies them with more alcohol. He then places them into the doubled room to sleep it off. They are described as laying on the floor which appears to be a ceiling and they wake to a feeling of defying gravity and going to fall, since by their perception, they are stuck on the ceiling. Then he has them shut their eyes and he takes them to the regular room, there to try to reorient themselves. For these vulnerable people, perhaps they have permanently lost a sense of what is real and what is imaginary when it comes to their sense of the stability of gravity, something fundamental to a person’s sense of balance and orientation to their environment. In the final paragraph, the narrator speaks of expanding his “underhouse” and possibly he and his house removed from existence.

In terms of Freud’s arguments as to what makes the uncanny, aspects of this story appear to meet the requirements. However, for the story as a whole, I think it falls short. Freud begins his essay with a definition of the uncanny as “arousing dread” and “creeping horror,” the “terrifying” in the “familiar.” Defying gravity and being disoriented in space, especially for someone who reads a lot of science fiction, fails to meet the level of dread and horror required. It certainly creates some uncertainty as to reality, and evokes some sense of infantile helplessness. But the truly uncanny, something truly unescapable and terrifying, requires more than this temporary disorientation or momentary repression. And this modern “unheimlich” falls short of uncanny literature as defined by Freud.

Thanks, Dr. Arnzen, for giving us this opportunity to contribute to your blog.

The story I’m reviewing is “Dolls’ Eyes” by A. S. Byatt. Just from the title, you can see Freud’s laundry list of the uncanny. However, there is more to this tale than just dolls and the fear of the double.

In the story, Fliss is a woman who has never been in love and lives a solitary life, surrounded by her dolls. The dolls are her only real friends, until Carole Coley shows up. Carole is a new teacher at Fliss’s school, and she moves in with Fliss for the remainder of the year. Fliss falls in love with Carole, a love which is ultimately betrayed when Carole takes one of her dolls and sells it on a TV antiques show. She uses the money to go on vacation, where she is involved in an unfortunate accident involving jellyfish that sting out her eyes.

Byatt’s description of Carole is interesting—she herself might be a doll. “Carole Coley had strange eyes; this was the first thing Fliss noticed. They were large and rounded, dark and gleaming like black treacle. She had very black hair and very black eyelashes.” It’s almost as if one of Fliss’s dolls came to life, and they fell in love. Freud noted that the doll harkens back to childhood, when the demarcation between reality and fantasy was not so clear cut. Fliss is presented as child-like; her name is a nickname from her childhood, and she’s never had a romantic relationship before.

Carole’s loss of her eyes is another item from Freud’s uncanny list. Interestingly enough, the good doctor contended that this fear was a substitute for castration anxiety. That makes it an interesting inclusion in this story, which features female characters and is written by a female writer.

The final paragraph of the story, where Fliss tells the dolls of Carole’s face and they “make an inaudible rustling, like birds settling” also draws on Freud’s fear of confusions between reality and imagination. You might even say that, since Fliss called for the doll to exact retribution from Carole, the story delves into the all-controlling evil genius.

“Dolls’ Eyes” succeeds in highlighting Freud’s ideas about the uncanny in literature, but does it succeed as uncanny literature? It’s not particularly fear-inducing, so in that regard, I would say no. It’s well-written, and an interesting response to a prompt, but the problem is that the ideas here are so worn out that they fail to produce an emotional response of dread in the reader. By the time you have a horror movie parody of an idea (Chucky), it’s fair to say that a writer would have to do something pretty radical to make the idea frightening again.

Perhaps that is the most valuable lesson to be taken from this story, and this collection. The stories are all interesting as a study of how writers try to update an idea, and given the field of writers there’s not a bad story here, at least not from the technical standpoint. However, very few produced feelings of dread or horror. Of course, those feelings are subjective, so perhaps others will have the complete opposite reaction. One thing is sure—in order to use these themes in a story today, a writer not only needs to write well, but also needs to update the idea in some way to make it fresh again. How the writer does that (Use video game characters or virtual pets? Write modern day stream-of-consciousness a la James Joyce, but for the cyber set?) may vary, but the ideas have to be relevant in order to truly horrify.

Thanks, Mike, for allowing us this venue to post our thoughts on how Sigmund Freud’s “Das Unheimliche” (translation: “The Uncanny”) has been interpreted by today’s writers.

The story I read was Adam Marek’s “Tamagotchi,” which is a take on Freud’s analysis of the horror of dolls appearing to be alive. A reader might also see a bit of Freud’s theory of the fear of an evil or supernatural force in this story.

In “Tamagotchi,” we see the effects of a virtual pet on a man, his family, and his world. The narrator, the father of a child with an autism-like condition (we never are given a name for the son’s actual diagnosis), buys his son a Tamagotchi, which is a little computerized pet. Unfortunately, the pet gets AIDS (the father’s diagnosis) and torments the family, most especially the father.

Marek updates Freud by using this trope as an analogy for a father’s fear of his son’s condition. Like his son Luke, the Tamagotchi, named Meemoo, socially isolates itself. Meemoo is not wanted around other Tamagotchis, and Luke is not wanted around other children. Also like Luke, Meemoo has a condition that can be diagnosed, but never cured. People are afraid that Meemoo’s disease might be catching, just like Gabby, Luke’s mother, fears that Luke’s condition might also lurk in the baby she carries in her womb.

Yet, perhaps the most terrifying similarity is the end result of our story. Unable to starve Meemoo to death – to get the limbless, sore-ridden 30-pixel creature out of his life – the father leaves Meemoo to suffer and die in the rain. Just like he wishes he could leave his son out in the rain, taking the burden of a not-normal child out of his life.

This is how our modern understanding of “The Uncanny” has developed. What frightens us is not the uncanny as much as the alienation we experience from our association with the uncanny. Because of his son, because of the toy that morphs into an animate object, our protagonist is forced into a life where he’s not even accepted at a child’s party. Nothing is more frightening than being a pariah in society. We all want to belong.

As for if this work succeeds as being a work of uncanny literature, yes. And no. After reading “Tamagotchi,” we are left with a feeling of unease. However, we are not repulsed by the Tamagotchi, but rather by the father’s feelings toward his son.

It’s happened to all of us at one time or another. We’ve wished for something, maybe didn’t even articulate our wish, because it wasn’t something we could have actively allowed ourselves to have. And then it happened.

Uncanny.

In Jane Roger’s “Ped-o-Matique,” this is precisely what happens to Karen. All she has left of a failed relationship is her son Zac: “Her mother wanted her to meet a man. But I’ve met the man, Karen said to herself. I’ve even had his baby.” Her career is going wonderfully, she’s been selected to travel from Australia to deliver a paper at a conference in Paris. She spends the entire beginning of the book telling herself this is where she should want to be. She is weighed down impossibly by the word “should,” she should have had the sense to end her relationship with “P” (she can’t bring herself to use his full name), she should be honored to go to this conference, she should live in the now. But all she wants is to be at home with her baby.

The uncanny piece in the story is the “Ped-o-matique”, an innocuous free foot massaging machine in the Singapore airport. With a half hour to get to her gate, she steps in to use it. Sits down, tells herself she should relax, reminds herself that the massager can prevent deep vein thrombosis in flight. But it doesn’t stop. She can’t get her feet out. She is trapped, and the apprehension she feels builds to terror, as she screams and cries. It’s easy to say, “why did she panic in a crowded airport?” She wasn’t maimed, or even really hurt, but the thought of being trapped in a public place, the shame of not being able to operate a machine that hundreds of other people can use just fine, would get to you, I’d think. I can imagine the frustration she felt. It’s terrifying. In his 1919 essay “The Uncanny” Freud tells us that “An uncanny experience occurs either when repressed infantile complexes have been revived by some impression or when the primitive beliefs we have surmounted seem once more to be confirmed.” Karen is repressing her desires to get home to her boy, “When she said she didn’t want to go, people had been incredulous. It was an honor—an accolade! It showed she was a real high flyer. Ha ha. And why would anyone in their right mind not go to Paris? Lucky her!” Even in the short excerpt, Rogers allows readers to see that Karen has no interest in Paris, doesn’t want to be there, just wants to be home. When, after screaming, weeping and wetting herself, Karen is finally freed from the Ped-o-matique bruised and relieved but otherwise no worse for the wear, she is offered the option for a later flight to Paris. She instead elects to fly home, “almost happy enough to dance.” Freud tells us “As soon as something actually happens in our lives which seems to support the old, discarded beliefs, we get a feeling of the uncanny.” Through these definitions, “Ped-o-matique” succeeds as a work of uncanny literature.

Rogers updates the story by placing it in an airport. Airports are generally ultra-modern, clean and safe places. This one had a pool, a cinema, restaurants…and of course the Ped-o-matique. An airport is a metaphor for our rushed, busy lives, the need for all this entertainment, all of it at our fingertips lest we sit in idle thought for too long. A mechanical foot massager is a luxury, Rogers describes the “squashy comfort” of the leatherette seat. It increases the sense of the uncanny by having the horror come from something that is meant to cause relaxation and pleasure. It’s so hard for us to relax these days that the thought of this kind of a swindle is deeply unsettling. This is an extremely urban story, one that capitalizes on our weakness for things that are easy and are handed over to us. It’s an interesting piece because of how little happens, Karen will probably laugh about this incident in a few months or years, but in the moment, all she could see was being trapped there forever and never seeing her son again.

Ian Ruhig, when tasked to write a short story in response to Sigmund Freud’s “Das Unheimlich,” updated the story upon which Freud based the foundation of his ideas on the uncanny in literature. ETA Hoffmann’s “The Sandman” tells through a series of letters the story of a man who begins to lose his grip on sanity after a encountering the man he believes killed his father, and it employs the use of eyes or blindness and automata throughout the story. Ruhig’s tale is that of a man who begins to lose his grip on sanity as he plays the part of spy, looking for student terrorists on a university campus, after choking his father to death. Like Hoffmann’s story, Ruhig repeatedly references eyes and eye pieces and includes the murder of the main character’s father, automaton behavior, delusions, removal of body parts or body parts as separate entities, and self-destruction. The story employs or at least references nearly all of Freud’s list of uncanny devices (which also helps link the story to Hoffmann’s and could be the only link Ruhig intended).

Perhaps this is why the story succeeds in breeding a sense of the uncanny even as it meanders towards the end. Like “The Sandman,” “The Un(heim)lich(e) Man(oeuvre)” takes more time than it needs to wend its way to the finale, but Ruhig seems intent on out-Hoffmanning Hoffmann. Entire passages relay nothing but stream-of-conscious literary allusions, cliches, puns, and rambling that certainly lends to the idea of an epileptic fit and even uses numerous repetitions of various ideas or allusions. The passages are useful in solidifying the idea that the narrator is mad or fast heading that way, but their length and frequency tend to feel like overkill.

The Freudian devices Ruhig employs occupy every corner of the story. The narrator has a doppelganger whom he refers to as a friend and separate being but who is clearly a figment of the narrator’s hallucinations and meant to represent the narrator’s mirror image. He describes the other students as if they are automatons and British descendants of World War II as dancing “English corpse-children.” He also refers repeatedly to the Masons, believes he is at university to spy for the government on would-be terrorists (and even meets with his “controller” to report suspicious behavior), hears imaginary children running about and shouting, and engages in other acts of delusion and beliefs of conspiracy.

The most obvious device Ruhig uses is the eye, fear of blindness, and the removal of the eyes. The narrator is the “eye” for the supposed government controller, and he alludes to art depicting “exoculation,” uses puns and nervous tics with eye imagery (“bug-eyed,” spectacles and monocles, “eye-campus,” etc.), and even removes his own eye at the end of the story. His father was an optician, and the narrator relates his father’s job with the utmost of uncanny: “I’d see a customer under that inverted pyramid of letters, wearing those iron-maiden metal goggles into which Dad slotted lenses like pennies.” The abundance of uncanny references does instill a sense of the uncanny but also creates a numbness to the discomfort when by the end the narrator finally performs his own “exoculation” with the help of his doppelganger reflected in the knife’s metal blade.

Ruhig manages to establish a very modern world in which technology can provide the impetus for a great deal of the uncanny we experience, from conspiracy theories regarding hidden evil puppeteers to security cameras watching and recording. Even binary code bytes, repetitive 0s and 1s, acting as section breaks (with some bytes repeated) throw the reader off balance. He establishes the uncanny, as Freud defined it, as alive and kicking in spite of the technology and knowledge that has allowed society to do away with the superstition Freud believed forms some of our reaction to das unheimlich. Unfortunately, he does so by beating the reader over the head with the uncanny devices with enough redundancy to deaden the reader’s engagement with the story.

I think that Matthew Holness takes a very disturbing spin on the subjectivity regarding several of Freud’s causes of fear that are displayed within literature: the concept of being buried alive, mistaking inanimate objects as animate, and confusions between reality and imagination. These three sections of the Freudian Uncanny are interwoven within the story in a modern setting as the narrator struggles with his ventriloquist dummy, the Possum. In regards to the author “updating” his work to Freud’s theories, I think he does an admirable job relating present obstacles to past problems. It is obvious that our narrator, no matter how reliable he is, is dealing with a reoccurring ghost from his childhood that he sees and continues to experience through his puppet. He treats it as if it were alive, and one has to question whether he literally believes that it is – now keep in mind the whiskey that he continually drinks throughout the story may or may not have something to do with the fact that he is confusing reality with his imagination. Because he views the Possum as an enemy of his past, he feels that by burning the puppet, and or burying it alive in his case or drowning in outside in the shed, that this will vanquish the terrors that he went through as a child, which appear to me to be some sort of physical or sexual abuse.

I found myself constantly comparing the narrator to Norman Bates in the sense that he drank a lot, and spoke about Christie in an uneasy way, as if he both loved him and held at grudge against him at the same time. I definitely felt an oedipal triangle starting to form between them and what the puppet represented to our narrator, and I’m not sure if Christie was really alive, or was just a infatuation like Norman had with his mother.

Overall, I think the story succeeds as a work of uncanny literature because it not only touches on Freud’s ideology regarding fear in several instances, but it brings in other aspects of uneasiness that add to the piece as a whole. For instance, the setting itself was very disturbing to me because it exhumed an atmosphere that was taken over by filth and disease. I know at one point, the narrator says that he licked the dead flies off of the Possum, and there was another instance where his bloodied, Eczema hands were wading through the puppets ashes as a reassurance that it was destroyed. Take this setting and couple it with some suppressed childhood anger/anxiety and you have yourself an uncomfortable winner if you ask me.

I believe that uncanny literature today expresses hidden fears that adults don’t want to acknowledge because they think they have conquered them throughout the years. A lot of issues that we tend to block out in our childhood ultimately end up reoccurring throughout our lives, and by reading pieces that confront those issues head on, can be quite dramatic to some readers. I think the part in Holness’s story that really stood out to me was when he actually got into a fight with the Possum, and ended up beating it to ‘death’ and severing its head from its body. Clearly, there was some suppressed emotional/violent turmoil going throughout our narrator’s head that caused him such pain and anxiety that he felt the need to literally destroy this representation of his fear(s).

“Anette and I Are F**king in Hell” by Etgar Keret is the final story in “The New Uncanny.” Barely a page and a half, this story is chock full of imagery, most of it stomach churning and painful. But is it uncanny? Let’s see.

Freud published his article “Das Unheimlich” (The Uncanny) as a list of frights that go above and beyond the normal scare. To Freud the uncanny at first seem unfamiliar, but then the person experiencing the horror has a revelation of something they’ve perceived or felt before. From “Applied Psycho-analysis The Uncanny” Freud writes: “…for this uncanny is in reality nothing new or foreign, but something familiar and old-established in the mind that has been estranged only by the process of repression.”

Freud provides several very specific examples of what constitutes the uncanny: fear of losing one’s eyes, fear of inanimate objects coming to life (dolls being the most obvious), fear generated when numbers reoccur too often, fear of the automatic mechanisms of the body (epileptic seizures are the example Freud provides), etc. The introduction of “The New Uncanny” provides an excellent list of these on page viii.

So, is Etgar Keret’s story uncanny? The action of the narrator and Anette being unable to control themselves and giving into their carnal desires even though they are disgusted by them fits the mold of the uncanny. From page 221 and page 222 of “Anette and I Are F**king in Hell” Keret writes: “And there’s another special thing about this terrible place – you have a constant hard-on, if you’re a man, and if you’re a woman, you’re always wet, and the whole sex thing turns into an almost involuntary act, like breathing, like breathing moldy air that makes your lungs convulse as if you’re about to puke.” Later in the story on page 222: “Our shame and suffering delight them, and we can’t stop. If only I’d listened to the preacher when I was a kid, if only I’d stopped when I still could.”

So, sex is reduced to no more than breathing or blinking in this story. It’s more than compulsory, more than an addiction, if you come in contact with any other being in Keret’s version of Hell then you will f**k, all while imps and bats and sulfur and ash surround you.

The setting however takes away some of the uncanny. Freud writes: “I cannot think of any genuine fairy-story which has anything uncanny about it.” He continues: “This may suggest a possible differentiation between the uncanny that is actually experienced and the uncanny as we merely picture it or read about it.”

Freud is pointing out that in a completely fictional story, fairy-stories being his chosen example, when normally uncanny things (animated dolls, the dead coming back to life, etc.) occur, they don’t seem uncanny because in whimsical tales these events are expected. The reader shouldn’t be surprised by events happening that transcend normal reality.

In a story set in Hell, anything can happen. Hell has some stereotypes about it: fire, sulfur, eternal suffering, lakes of fire, demons torturing souls, etc. Some of that is present in this story, but Hell is not a normal setting, thank God. Had this story taken place in a high rise office and everyone ripped off suits and skirts and gave into carnal desire with no thought to consequences and no one could explain it, the level of uncanny would have risen. As it is here, the setting being one of pure fiction the reader has less a feeling of the uncanny, even though the grotesque landscape does make the reader feel sorry for the characters trapped there.

In the introduction to “The New Uncanny” by Ra Page, this is written on page xi: “And one writer, Etgar Keret explored a cause rather than a symptom of uncanny anxiety: Freud’s ‘fear of sex’.” I must confess I am not an expert on Freud. Fear of sex is not explicitly listed as one of the elements of the uncanny, but I won’t argue with the notion that Freud had issues with sex.

Ultimately this story is a little uncanny, but I would argue 100 years of medical advances may have rendered Freud’s uncanny fear of “the feeling that automatic, mechanical processes are at work, concealed beneath the ordinary appearance of animation.”

Freud equates epileptic seizures with madness. That notion is not accurate today. Freud refers to “omnipotence of thoughts, instantaneous wish-fulfillments, secret power to do harm, and the return of the dead” as notions that are old fashioned and not accurate anymore in his own time: “We – or our primitive forefathers – once believed in the possibility of these things and were convinced that they really happened. Nowadays we no longer believe in them, we have surmounted such ways of thought ….” Similarly the idea humans are nothing more than automatons or flesh-bots has been rendered laughable or arcane.

Keret uses uncontrollable sexual urges as the automatic function that damns his narrator and Anette to an eternity or grotesque coupling with the worst audience an exhibitionist could ask for. It would be convenient, especially for men, if sexual urges were uncontrollable. Imagine how much infidelity and how many affairs could just be explained away. Now imagine the cheated upon person listening to those arguments. Freud’s “castration complex” then becomes much more real for the cheater.

“Seeing Double” by Sara Maitland

In her short story, “Seeing Double,” Sara Maitland updates Freud’s theory of the Uncanny by injecting the exploration of gender roles. The uncanny can relate to a double. In this case, the double is a female version of the main character, the son. (No one in this story is named, probably to give an anonymous, blank feeling to the characters.) The second self is a female, one he is constantly stuck with because it’s in the back of his head.

When he first sees the second face in a mirror, he recognizes his mother’s blue eyes. He has taken on the identity of his mother, who died in giving birth to him, but in doing so, he has killed her. He has an emptiness caused by the lack of a mother that his second face in a sense fulfills.

“All women have double mouths, he thought, then he thought that he did not know where the thought had came from.” This is, no doubt, referring to the vagina, but at that age he wouldn’t have known that so we have to presume that the thought comes from some collective unconscious. Soon after, the second face begins to speak to him, but he’s the only one who hears it. This may point to the fact that he is schizophrenic, a characteristic we can refer to as uncanny.

Before the onset of puberty he thinks that the second face is kind of fun. He’s never alone and he always has a friend. But once he achieves puberty, he grows very uncomfortable with his double face. Is that because it’s female? Would he have felt more at ease had the second face been male? She prevents him from having any secrets. She hates it when he masturbates, trying to distract him by yelling at him, calling him “pathetic and disgusting.”

The tipping point comes when he falls in love with one of the maids. His second face calls him a freak and tells him no one will ever love him back. This is symbolic of someone who feels that having too much emphasis on his feminine side makes him a freak and therefore unacceptable to society.

According to Freud, “…everything is uncanny that ought to have remained hidden and secret, and yet comes to light.” Repulsed by his son’s feminine side, the father tries to hide the second face from his son as long as he can. To counteract that feeling, he gives the second face a special kiss every night. The father may also be uneasy because the second face is an echo of his mother’s face, particularly in its big, blue eyes. Perhaps, the fruit doesn’t fall far from the tree and the father struggles with his own gender identity, making the presence of the female face particularly uncomfortable for him because he tries to suppress the feminine side of himself.

When the son shoots the other face, he’s killing his feminine side, which in the end destroys him.

I think the story is uncanny up to the point that the boy’s second face becomes a sarcastic nuisance. At that point it slips into a kind of satire of gender roles. It works on a symbolic level but it loses its scariness. Also, I couldn’t get beyond that fact that the boy doesn’t know he has a second face until the maid tells him at the age of twelve. Doesn’t he wash the back of his head? Doesn’t he feel it when he sleeps on the second face?

I don’t think the ending is in keeping with the rest of the story. The son would have to realize that in shooting his double, he is also killing himself. Though he is annoyed by her, in the story he isn’t driven to the point of desperation that would make him take such an extreme act.

The story teaches us that in today’s culture, secrets that used to be hidden come into the light and cease to be uncanny. We no longer have the mysteries we had a century ago.

“Long Ago, Yesterday”

1. How does the author try to “update” the Freudian Uncanny in this story?

2. Does the story succeed as a work of uncanny literature?

3. What does the story teach us about the Uncanny in today’s culture?

I looked for examples of the familiar turned uncanny. Here’s what I came up with. This story takes the familiar idea of a family. It is made uncanny because the family in the story is dead. In the first paragraph, the narrator says that he saw his father at a pub and was “almost ecstatic, to see the old man again, particularly as he’d been dead for ten years, and my mother for five.” The narrator is almost the same age as his father and the father does not recognize his son. Furthermore, the narrator says that he has some of his “best friendships with the dead.” On page 395 of “The Uncanny,” it’s explained that “Many people experience the feeling in the highest degree in relation to death and dead bodies, to the return of the dead, and to spirits and ghosts.”

Just because Billy is hanging out with the ghosts of his parents does not seem like enough to categorize this as uncanny. I think it’s his relationships with the “ghosts” that are important. Billy seems to be reliving a negative past with his mother. “I stood in my usual position, just behind Mother’s chair. Here, where I wouldn’t impede her enjoyment with noise, complaints, or the sight of my face […].” On the other hand, his relationship with his father is bizarre. Here are some of the most memorable examples: “Dad was my ideal. He would read even in the bath, and as he reclined there my job was to wash his feet, back, and hair with soap and a flannel. When he was done, I’d be waiting with a warm, open towel.” Father and son have a discussion about the son being a homosexual and how the father is unsatisfied with his own sex life. “I had been Dad’s girl, his servant, his worshipper [..].” “Naturally, she couldn’t wish for us to die, so she died herself, inside.” “He [the father] had taken her sons for himself, charmed them away, and he wasn’t a sharer.”

This seems to be a twist on the classic Oedipus Complex, where the child wants to possess the parent of the opposite sex and get rid of the parent of the same sex. In this case, Billy should want to get rid of the father to be with the mother. But that’s not what is being described. Billy seems to have a much closer relationship to the father. But, I think it’s the father who wants to “possess” Billy. The father even says, “I am hoping she will die before me, then I might have a chance… […].” The father also says that “There’s a lot you can put in a kid, without his knowing it.” Perhaps this is trying to offer an explanation about the son’s homosexuality and that it actually comes from his father.

Overall, I do think that this works as a story of the uncanny. It addresses some of the ideas from “The Uncanny” and seems to successfully put a new twist on them. I don’t know if it really fits as horror though. Sure it deals with taboos and ghosts. But I don’t really see this story as scary. There is a lot of potential for psychological examination and Freudian interpretation; I just don’t see it as a strong horror story.

I think the story shows us that the Uncanny persists in today’s culture. It may not be a traditional view of the uncanny, but it is still a valid one. Just as the times change, so should our psychological interpretations.

My review was on the story “Dolls’ Eyes” by A.S. Byatt. In this story a thirty year old school teacher named Fliss is examining her life and her lack of having felt any love or closeness with anyone. She also, in the beginning of the story, calls herself “odd,” though she is unsure exactly what she means by this. She has inherited dolls from her mother and grandmother and people have given her dolls as presents, because they thought she was collecting them. Her house is filled with over a hundred of these dolls. She moves them around quite frequently, but never plays with them. When she moves them to different locations she says she is giving them “different company” and she believes “that some of them were alive in some way” (108). This is the aspect of the uncanny in this story that I’m going to focus on.

It is this initial feeling of the dolls being alive that Byatt uses to create an uncanny feeling in her story. Freud speaks of the use of dolls or automatons as “recollections” of childhood, and that “the idea of a ‘living doll’ excites no fear at all; the child had no fear of its doll coming to life it may even have desired it” (386). And Fliss, who’s only friends are the dolls she lives with, is a prime example of this behavior. She does not fear the ‘aliveness’ of her dolls. Fliss is, in fact, rather doll-like herself. She lives in solitude with these dolls; her only contact is with the children she teaches and her co-workers. She does take in boarders, which is how she meets Carole Coley, a woman who seduces her. Once Carole comes into the story another of Freud’s inferences of the uncanny is introduced, that of the “eyes.” Byatt stresses the strangeness of Carole’s eyes, “large and round, dark and gleaming like black treacle” (109). Even Carole’s dog Cross-Patch is named for the “eye-patch in black on a white face” (109). It isn’t until Cross-Patch destroys the baby doll Polly that the doll’s eyes take effect in the story. Polly is an “alive doll” and the dog completely destroys her. The destruction of Polly’s eyes is described in great detail: “The rattling noise was Polly’s eyes, which had been shaken free of their weighted mechanism, and were rolling round inside her bisque skull. Where they had been were black holes. She had a rather severe little face, like some real babies. Eyeless it was ghastly” (113).

Later in the story after Carole’s betrayal of the love that Fliss has for her, the first love she has ever felt towards anyone, Fliss calls on the ‘spirit’ of the doll for vengeance. This is a bit of irony in the story when Fliss initially asked the doll to bring Carole back to her, when Carole says she needs to go away for awhile and takes Polly with her, “Before she left, in secret, Fliss kissed Polly and told her ‘Come back. Bring her back’,” and later she curses Carole by saying, “Polly…Get her. Get her”(119).

Byatt updated the Freudian uncanny in this story by making it about two women, one who has never loved, but wants to, and one who is a manipulator and deceiver. She uses popular television shows, such as “Antiques Roadshow” and uses independent women with careers as main characters. Byatt uses Fliss’s innocence to capture the horror and dread of the final act of the story. Fliss, in her childlike love for her dolls, recaptures her childhood by believing that the dolls have life in them. Only a childlike imagination can justify belief that certain dolls have life while others do not.

I believe this story definitely succeeds as a work of uncanny literature. It is the dread that Byatt evokes in the innocent belief that Fliss has of some of the dolls being alive:

“She knew, but never said that some of them were alive in some way…” (108)

“You could even distinguish, tow with identical heads under different wigs and bonnets, of whom one might be alive…and one inert” (108-109)

“This doll was called Priddy, and was not, as far as Fliss knew, alive. She also borrowed the rigid Sarah Jane, who certainly was alive.” (111)

“Polly was Polly again, only fresher and smarter. She rolled her eyes at them again…” (115)

“The dolls made an inaudible rustling, like distant birds settling.” (121)

I found the use of the word “inaudible” interesting. Byatt again stresses an uncanny feeling by using Fliss’s ability to hear an inaudible rustling sound which the dolls have made in acquiescence to the knowledge of Carole’s misfortune.

In today’s culture we like to say that we have seen it all and not much is as horrifying as it used to be, but I disagree. Yes, we probably have seen and read it all in one form or another, but we keep going back for more. This is why I disagree and why I think this story works as uncanny literature. Some may find this story does not create dread or terror for them, but there are others who may read this story and find it unnerving. These are the people who will wake up one night and pull the covers a little tighter around themselves, because they know they heard something moving in the dark. These are the ones who are going to go room to room and make sure their children’s dolls are where they are supposed to be. The uncanny in our culture has not changed as much as we think it has, our fears and dreads are still there when the darkness comes.

The “Double Room” by Ramsey Campbell is rather a sad account of a recently widowed, fat old man, who rather than cancelling a hotel stay in a town he and his wife used to like to vacation at, decides to go it alone after her death. We first meet Edwin Ferguson in the bar of the hotel where he is trying to flirt and pick up two girls attending a convention. Not only is he unsuccessful, he comes off as a pathetic letch. The reader is given to viewing him in a poor light, as we do not know unitl about the middle of the story that he recently lost his wife.

A couple elements of the uncanny, the double, and unreality being confused with reality, come into play after he leaves the bar and arrives in his room for the evening. Edwin discovers, in a rather discomforting scene in the bathroom, that every action creating a sound he makes is mimicked by someone or something on the other side of the wall in the next room. Even the words he speaks are replayed back. As it continues, he becomes increasingly unnerved.

Edwin cannot believe that this is anything but the neighboring guests tormenting him, even after he is informed the room is unoccupied and a search of room by hotel staff reveals that no on is or has been in there. He begins to talk to the wall but instead of being mimicked, similar sounding phrases are returned but with words slightly different, accusing him of loathing his ill wife and wishing her to die. Even when he desperately tries to turn off the voice in the next room by not speaking, it continues with accusations he eventually tries to deny. He finally can’t take it any more and admits out loud to secretly wishing and praying for her death, “but only for her sake”.

I felt the unease of the uncanny on a couple of levels. Before we find out that the room is unoccupied, I wondered who whoever it was in the next room was able to copy his sounds and movements – could the room be bugged or fitted with a camera? This certainly was too practical. More fitting was the idea that he was mixing reality with imagination due to paranoia resulting from his loneliness, jealousy and inability to be accepted by the revelers of the conference. Even though he was the one being tormented, he now was also “the center of attention”.

However, once it is disclosed that the room is empty, and that the voice does not mimic but accuse, the unease of the double enters the picture. It was his conscience picking at his guilt of desiring to seek a carnal fantasy, just after the death of his wife whom he secretly wanted to be free of. We are also left with another possibility: was it his deceased wife haunting him? The voices presented are always muffled, in several cases he can’t determine the gender. I thought it interesting that in the first instance of a dream utterance, he heard the voice say “Livadeth” instead of Elizabeth, i.e., live-a-death.

On last aspect of the uncanny in the story is the hotel itself. While being familiar and perhaps once comfortable to Edwin, it became stark, cold and uninviting (unfamiliar) during this stay without his wife.

The Uncanny of “The Sorting Out”

The story I was assigned to respond to is “The Sorting Out” by Christopher Priest. For those of you that haven’t read it, I’ll give you a summary as best I can. This story is basically about the aftermath of a breakup. The female character of the story is called Melvina and she has somewhat recently broken up with her live-in boyfriend Hike. She comes home late one evening to find her front door standing wide open and bashed in. She stands on the edge of the doorway, listening for any movement inside, listens for something outside and decides that whoever broke her door down is probably gone.

Even though the house betrayed no one with a squeak of the stair or floorboard, Melvina still does a room by room check of her house, as I am sure anyone would do. As she does her room by room check, she sees little reminders of Hike, a stray painting, a misplaced magazine or two. But finds nothing more. No one is hiding in the house or in any dark corner. On top of that, she cannot find that anything is missing. In fact, at first, the front door is the only thing that appears to show any sign of a break in at all. But, she is still set on edge; something is wrong.

When Melvina finally comes to terms that there is no one in the house she decides to look closer, and as the saying goes, the devil is in the details. Through the searching of the house, we find out that Melvina is a book collector of sorts. She is very meticulous about the order in which she stores her books and more importantly how they are stored. She discovers that her order, the thing she holds on to so dear, is interrupted. Instead of finding her books lined up on bookshelves, the books are stacked in random order and the ones with dust jackets are put back together the wrong way, the jackets are on upside-down.

The most bazaar thing that happens occurs when she is in her office. She thinks she hears someone hiding behind the curtain. She can tell by the way the curtain is moving that something is there, something that shouldn’t be there. She hears breathing or some other noise. On top of that, the something has one of her books. She creeps over, wooden ruler in hand and smacks at the book, it goes flying but she isn’t done. She rips the curtain back only to find nothing. Only the window is ajar and a breeze is coming through.

While she’s at the window she sees a car and thinks that the person that has messed up her order is waiting in the car. She runs out to investigate only to find the car empty. She turns back to her house and realizes that she left the door open. She does another check of the premises and is finally satisfied that no one is in the house. She finally drifts off to sleep only to be awoken by a book smashing into her face. As she wakes, she sees no one, but hears a car speeding off. She goes to the window and watches the car drive off. Because of the scare, she is now fully awake. She decides it’s time to move forward and clean out her ex’s mess.

So, now that you’re more or less up to speed let’s look at how this relates to Freud. One of the points Freud highlights in his essay is coincidences and repetitions. The reason coincidences and repeated values can be considered uncanny is the frequency in which these coincidences or repetitions occur. In short, there’s something off about repetition. For example, if you go into a store and happen to see someone in the same aisle, you’d think nothing of it, even if they were an unsavory character. But if you saw that same person in every other aisle and they always seemed to be the same distance from you, you’d feel a little worried, perhaps thinking you were being stalked.

I think that this particular point is highlighted wonderfully in this story. Priest uses the repetition of the misplaced books to bring about a feeling of unease. Someone had to place the books that way, otherwise Melvina wouldn’t be scared. I can relate to her, I am someone that likes my books in order and I have occasionally found my hardbacks with the dust jacket on upside-down. This is strange when I find this because I am the only one who reads my hardbacks, but if I found every single hardbound book with a messed up dust jacket, I’d be a little freaked out. Priest uses this freaky feeling to put the reader on edge. He ramps up the tension by slowing down the scenes and letting us peek, just a little, into Melvina’s thoughts. We get to see how this is affecting her.

Because of that off putting feeling, I think this story adequately demonstrates uncanny literature. I felt unease; I was on edge because there was too much repetition of the book order for it to be a coincidence or accident. I found myself feeling her fear and paranoia, hoping she’d remembered to lock the door and check the hall closet. The strange thing is that this fear came from something small, something we wouldn’t think of if we found it in our own house once, a misplaced book.

I really think this story teaches us that the Uncanny still exists. We don’t need some high tech robot like in “The Sandman” to bring us a state of fear. We don’t need some elaborate set up to frighten us; all we need is our imagination. Our minds can fill in the blanks. I do think that if someone with just a slight case of the crazies were to read Freud’s essay, they might be able to conjure some scheme to scare whomever they pleased.

Many of the stories in The New Uncanny deal with today’s culture. They pull Freud’s theory into our world. In “Seeing Double”, rather than pointing Freud toward our time, Maitland points Freud toward the past.

There is no specific setting given, no time period, no names of characters even. But the slight clues we are given are perhaps 18th or 19th century. The characters are perhaps a member of a Northern European or the burgeoning American aristocracy.

What is uncanny in this story, then, is not dependent on either Freud’s generation or ours. Instead, it transcends time and reminds us that what is uncanny doesn’t change with each new generation, culture, or technological advance.

In “Seeing Double,” the young protagonist finds on the back of his own head another face. This face is female, blue-eyed like his mother who died in childbirth, rather than brown-eyed like himself and his father. His first interaction with this other face is to be bitten – the pain is shocking enough to make him scream.

According to Freud, a double in childhood often “wears a friendly aspect” (pg. 389). An imaginary childhood friend, for instance, one whom a child often wishes would take on animate characteristics (pg. 386). After puberty, however, after we pass the ego in development, we repress that friendly double. The reoccurrence of it later is then uncanny, and fulfills one of two functions: to criticize and observe the ego and act as its conscious, to become “isolated, dissociated from the ego, and discernible to a physician’s eye” (pg. 388); or to engage in “all those unfulfilled but possible futures to which we still like to cling in phantasy, all those strivings of the ego which adverse external circumstances have crushed, and all our suppressed acts of volition” (pg. 388).

In this sense, the double face in “Seeing Double” works perfectly as uncanny. At first, as a twelve year old, the boy enjoys her presence. She is a friend, and he’s never had one before; she’s someone to play with – the animate fulfillment of his imagination.

After puberty, however, she morphs into the first of Frued’s uncanny roles. She becomes the observer, criticizing and mocking the boy, taunting him with his own insecurities and base desires. Rather than allowing him to indulge in those baser desires, as a double in the second of Freud’s uncanny roles would have done (i.e. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and The Picture of Dorian Gray), this double reminds him how wrong and unacceptable his desires are. She screams “Freak, freak, freak!” while he masturbates, convinces him no woman will want him.

However, this is the point where I, as a reader, stopped feeling a sense of the uncanny. The last third of the story falls into cliché, finally ending with the boy killing himself to kill his taunting double. This, however, even continues Freud’s theory, as the double was, in fact, “the ghastly harbinger of death” (pg. 389).

“The Dummy” by Nicholas Royal is a fractured-perspective story about a novelist whose life is turned upside down after an affair. The first section of the story, told in the second person, sets up the doubling that continues until the end, successfully creating a feeling of unease and dread. The doubling is made modern by the way that Royal “twins” the reader with the protagonist and the way that Belgium is a “parallel world” to England (p.60).

In it, the reader is pulled into the narrative as an active participant, mistaking a fallen traffic dummy for a man, and then, upon discovery of the mistake, clandestinely putting the dummy into the passenger seat of the car and driving home.

The story then shifts to first-person and the mirroring continues. Here, the writer (the reader), tells the backstory that leads up to incident with the dummy. He (we) is sitting with his (our) new lover, explaining why he (we) love Belgium (p.59-60) and it becomes clear that the affair with Hilde is more than a one-night-stand.

Then we are back in the second person narrative, about to leave our suspicious wife for a while, and go to Hilde. Coincidentally, in the novel we are writing, our main character is also having an affair. We return; our wife confronts us with the knowledge of the affair. We go to a bar. On leaving, we see the dummy in the car and for a moment, we wonder whether or not we put up the hood of his jacket. After some time, we find ourselves in a hotel, and in a brilliant but very subtle twist, we realize that the protagonist is in fact the dummy – perhaps as the pain in the chest suggests, we have switched places with the dummy. And we, the new protagonist, go on with an undisclosed plan to harm the children.

At this point, one can’t help but remember the protagonist showing Hilde the picture of the children . . . the one that “went everywhere with me” and “was a year old.” (p.60) The effect is one of horrific déjà-vu, calling to mind what Freud said about the Uncanny. “. . . the uncanny is in reality nothing new or foreign, but something familiar and old-established in the mind that has been estranged only by the process of repression.” (Freud p.394)

Did he (I) murder the children before or after the affair? Is this story told in a linear progression? Did it happen at all or was it the product of a mind desperately trying to suppress the memory of his children and experiencing distress at each reminder as Freud would theorize? “In the first place, if psycho-analytic theory is correct in maintain that every emotional affect, whatever its quality, is transformed by repression into morbid anxiety, then among such cases of anxiety there must be a class in which anxiety can be shown to come from something repressed which recurs.” (Freud p. 394)

The switching of the protagonist for the dummy and then for the reader suggests that we are all exchangeable and disposable. The final revelation that the narrator was the dummy all along further suggests that what we think of as a consciousness, soul, or essence, is not at all unique. Even more disturbing, perhaps it doesn’t exist at all.

This story is an excellent examination of the Uncanny. The only parts that I would change are the sections that are written in the second-person. The story would work just as well (if not a little better) if those sections were written in the third- person instead.

In Continuous Manipulation, Frank Cottrell Boyce utilizes the ongoing technological advances in the video gaming industry in setting up his story of the uncanny. In direct correlation to the theme of “…doll[s] which appear to be alive” (Freud, 10), Ruthie figures out how to make her real, dysfunctional family mimic the life she creates for her “doll” family in the video game. The video game family also acts as a double (Freud, 11) of Ruthie’s true family, so as she manipulates the game characters, the real people around her act accordingly.

Continuous Manipulation is a successful work of uncanny literature because it fits within the definition of uncanny as “…belong[ing] to two sets of ideas…what is familiar and agreeable, and on the other, what is concealed and kept out of sight” (Freud, 5). The dysfunctional family is a common situation that is readily identifiable in our society. Moving away from a childhood lover and knowing that that person has influenced our lives forever is not uncommon, either. Our first view of Sue is one which could be any of us. She has a new boyfriend and is trying to get to know him by relating bits and pieces of her childhood and him his. Even when Sue admits she has a compulsion to visit her old boyfriend, Peter, the reader believes this is just the desire to see an old friend, perhaps to see if he is as affected by her absence in his life. It is not until we see Sue becoming more aware of the correlation between the video game and the actions of Ruthie’s family that we realize something is amiss.

As the story unfolds, we begin to understand that Sue has been directly manipulated by Ruthie as another character of the game, such as when she feels her exciting new boyfriend‘s questions “[seem] like moves in a game [she] does not want to play anymore” (Cottrell, 210). Sue’s visit to their home was likely directed by Ruthie, because maybe she wanted to see Sue. She was the one responsible for showing Ruthie how to play her video game in the first place. Only because Ruthie wanted her home life to go back to the way it was and stay that way forever had she removed Sue from Peter’s life so he would remain at home. However, she does not dislike Sue so she gives her some enjoyment in the form of other boyfriends, even if Sue is unable to stay with them and find everlasting happiness.

This story could be an admonishment against disregarding the effects of major life changes on children. Everyone around Ruthie went on with his or her own life plans and had no understanding of what the things that were happening meant to her. Had someone taken the time to explain why her parents were splitting up and why her father was getting a new wife and why Peter had to leave home to attend college, perhaps her frustration would not have morphed into an obsession with her video game, where she controlled the world and the events in it. Although Ruthie’s ability would not belong to a real child in our culture, there are many more diversions available in which a kid could drown their confusion.

Works Cited:

Cottrell, Frank. “Continued Manipulation.” The New Uncanny. Ed. Sarah Eyre and Ra Page. Great Britain: Comma Press, 2008. 207-219. Print.

Freud, Sigmond. “The Uncanny.” Rohan Academic Computing. 2 October 2009. http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/~amtower/uncanny.html

Gerard Woodward’s “The Underhouse” made for an interesting inclusion in the compilation “The New Uncanny.” Sara Eyre and Ra Page, the compilation’s editors, sent fourteen writers Sigmund Freud’s essay, “The Uncanny.” In this essay, Freud discusses how some fiction achieves “a special core of feeling…within the field of what is frightening” and outlines eight tropes commonly used to evoke this feeling of unease in readers.

The fourteen writers were asked to use the essay and the tropes outlined as a guide in writing works of short fiction for the compilation. Of these eight common tropes, Woodward’s focus was primarily on Freud’s discussion of the Double and the intentional blurring between reality and imagination.

The psychological creation of The Double, as a trope or archetypal pattern outlined by Freud, is “insurance against the destruction of the ego” and is coupled with a “belief in the soul and with the fear of death.” Woodward’s narrator becomes obsessed at an early age with a doubled world he enters by viewing the real world turned upside down. He “desperately wants to explore this exotic [world]” and is “profoundly disappointed” every time he’s forced to return to reality at his parents’ behest.

As an adult, he realizes he can finally create his upside-down world and prevent his own death. The story then becomes a How-To manual for creating our narrator’s double world. He describes various features of his model room upstairs and how he goes about duplicating the doubled (and reversed) features in the room immediately beneath it. First he duplicates/reverses his model room’s dimensions, then the floor, the rugs, the furniture, and even the curtains and chandelier.

Freud says this desire for doubling springs “from the soil of unbounded self-love, from the primary narcissism which dominates the mind of the child.” The story’s narrator supports this when he says “[it] was as though my life was a reflection in a pool…as though narcissus [sic] could indeed embrace his own reflection.”

Freud goes on to discuss that the manner in which the Double operates is reversed as a child matures. “[When] this stage has been surmounted, the ‘double’ reverses its aspect. From having been an assurance of immortality, it becomes the uncanny harbinger of death.”

The story’s narrator follows this same maturation process as he decides to duplicate, not just a single room, but the entire house. This process will take him “many, many years, and … I may not live long enough to complete [it].” The Underhouse has become the ticking clock of the narrator’s own mortality. But Freud’s “harbinger of death” portends a death that has prospects of being a grand adventure.

And as Freud notes, “there are also all the unfulfilled but possible futures to which we still like to cling in phantasy[sic].” And so our narrator ponders what would happen if he finished The Underhouse and it collapsed upon itself. “One must suppose that the two would cancel each other out…I would have folded myself out of existence. A rather attractive thought.” Our narrator is no longer immortal, and is now enthralled by the very real possibilities of his own impending mortality.

So how are we to make sense of the story in context? While Gerard Woodward’s “The Underhouse” is an interesting narrative that finds a clever way to implement a discussion of Sigmund Freud’s concept of the Double as outlined in “The Uncanny,” I’m not sure it elicits the unnerving or uncanny feelings that Freud identified in his essay. As a reader, I would have been willing to follow Woodward further into the story, if he were to have taken the narrative past his current jumping-off point and explored this doubling concept in greater detail, hopefully achieving the desired uncanny effect.

FAMILY MOTEL

Alison Macleod

This strange little short story was nothing more than a tease. Mia, the mother, was harboring deep feelings of guilt for not having wanted her first born. She looked for danger where there was none and blamed herself whenever Felix was in harm’s way. There was a lot of foreboding and unfulfilled foreshadowing in the story for nothing to happen.

Dan, Mia’s husband, Rosie, Felix and her have come to the States for a great aunt’s funeral. Their SUV has broken down, leaving them stranded at a little third rate family owned motel. They sarcastically call the owners the Earl and Mrs. Earl. Mia is unnerved when the owner keeps coming into their room whenever they’re gone. This builds suspicion and a sense of dread.

Combine this with her overactive guilt feelings and the tension builds.

Mr. Earl speaks to Felix once and tells him to stay away from the geese because they’ll peck his eyes out. Then when the youngster tells her that Mr. Earl has no eyes, the reader is left with a sense of impending doom.

On the first morning when Mia is out for an early stroll, she thinks that Mr. Earl is floating dead in the pool, although he shocks her by popping up his head. This appears to be a foreshadowing of disaster.

The following morning little Felix is missing. The reader presumes that either the geese got him or he’s drowned in the pool. Tension mounts even higher when Mia sees the pool gate open. The child is sleepwalking by the pool, however, and she scoops him up and carries him home.

Macleod pulled us into this era by setting it in a motel in New England with an in ground pool and emergency road service. She pulled us even closer with the use of required baby seats and air conditioning. The glass baby bottle dates it into the sixties—unless they’re still using them in England.

Mia’s guilt and the Earl’s eccentric personality helped to lend an eerie feeling to this piece; however, there was nothing uncanny about it. It did not succeed in giving the reader the slightest goose bump of fear. It actually left one wondering if a few pages might be missing.

Based on Freud’s premise it had potential that was never developed. It caught the reader’s attention several time, but then lost it in the ordinary.

This story teaches us that by today’s standards, the uncanny is lost in the mundane. It only whets the appetite for more, while teasing us with less.

Just a quick note to thank everyone in my class for posting the above responses to this book. This is a great study!