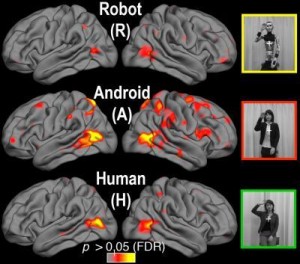

Scientists are continuing to conduct empirical research into the theoretical assumptions of uncanny valley theory. A recent article in Digital Trends by Jeffrey Van Camp announces that “Scientists think they’ve figured out the ‘uncanny valley’. It’s based on a report from Science Daily about a recent brain study called “Your Brain on Androids” by Ayse Pinar Saygin and others. Saygin’s group essentially tracked MRI scans of brains responding to alternating videos of humans and robots doing similar things — and concluded that “increased prediction error as the brain negotiates an agent that appears human, but does not move biologically, [may] help explain the ‘uncanny valley’ phenomenon.” Science Daily paraphrases it this way:

…if it looks human and moves likes a human, we are OK with that. If it looks like a robot and acts like a robot, we are OK with that, too; our brains have no difficulty processing the information. The trouble arises when — contrary to a lifetime of expectations — appearance and motion are at odds. “As human-like artificial agents become more commonplace, perhaps our perceptual systems will be re-tuned to accommodate these new social partners,” the researchers write. “Or perhaps, we will decide it is not a good idea to make them so closely in our image after all.”.

The “perceptual mismatch” described above is, at root, a matter of unresolved uncertainty, and the science here is in a way confirming an idea that is more than a century old. In one of the first theoretical musings about the uncanny itself in an essay by Ernst Jentch on “The Psychology of the Uncanny” (which predated Freud’s groundbreaking theory of the aesthetic). For Jentsch the concept of “intellectual uncertainty” was determined to be at the center of all feelings of uncanniness. “In storytelling, one of the most reliable artistic devices for producing uncanny effects,” Jentsch wrote, “is to leave the reader in uncertainty as to whether he has a human person or rather an automaton before him in the case of a particular character.” He also suggested that the brain can be “reluctant to overcome the resistances that oppose the assimilation of the phenomenon in question into its proper place.” Freud, too, followed up on this matter by theorizing the confusion between a symbol and the thing it symbolizes and suggested that the resulting feelings of unease were a matter of repressed wishes that were brought to life (predominantly the wish for an “omnipotence of thoughts” as much as any repressed infantile sexual desire).

In the quote from Saygin above, I found the notion that the brain “might re-tune” to the unfamiliar an interesting notion — that is, that as robots become domesticated (as “social partners”), they will no longer produce so much ‘intellectual uncertainty.’ Domestication is what renders the unheimlich familiar and predictable — a safe element of the experiential milieu rather than a threat that signals danger due to its uncertain status. Uncanny Valley theory suggests that the more “lifelike” an inhuman object becomes, the more creepy and scary it gets — so it is a moving boundary line of difference which is constantly renegotiated, the “closer” an Other object (robot/android/character) comes to taking on the aspect of the Self.

The question this raises for me is: When would the brain stop negotiating this boundary line between self and other? At what point does the brain perceive the Other as identical in status to the Self, erasing difference altogether? The tentative answer, I would suggest, is that such binary logics are at the root of the trouble here, and that social ideology steers this negotiation as much as the brain as a cognitive organ does. In other words, intellectual uncertainty cannot be detached from ideological uncertainty. And that’s why studying the uncanny as a cultural meme is just as important as it is to study it scientifically.

Saygin’s study — “Things That Should Not Be” — is available via The Journal of Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience.

Thank you for your thoughtful post. You are correct that what we may have measured may relate to much earlier concepts (in fact, we do cite Jentsch and Freud in the full paper, even though admittedly we don’t go into much detail given the venue is a neuroscience journal). The signals we measure though and the design of our experiments, for various reasons, allows us to access a less conscious kind of uncertainty, perhaps not completely analogous to intellectual and cognitive uncertainty (hence the term perceptual). But as a cognitive neuroscientist, I can address the question with the tools I have and can only specuate about the role of culture and society. I definitely agree with your last sentence, the uncanny valley is of interest from multiple dimensions and it is not merely a practical problem in robotics/animation, but a mirror onto human cognition, perception and more… Thanks again.

Thank you so much for commenting, Dr. Saygin, and many kudos to you on your research campaign. You’re doing important and fascinating work! I like your clarification about the distinction between intellectual and cognitive uncertainty…excellent point.

More articles on Dr. Saygin’s study have appeared in Wired and Boing Boing. The discussions by visitors on these sites are always interesting (and often a little nuts). One intriguing commenter compares the sensation of the uncanny to seasickness, which is a good comparison.