If you’re like me, you may have driven through tollbooths on an Interstate highway and noticed that Flo — the spokeswoman in ads for Progressive Insurance, has begun appearing everywhere.

The incessant repetition of product advertising across media breeds product familiarity. But it’s a familiarity that doesn’t always register until we encounter the advertisements again in places we don’t expect them and begin to suspect there is a superstructure at play around us that we are unaware of…an uncanny feeling of what Freud termed “the omnipotence of thoughts.”

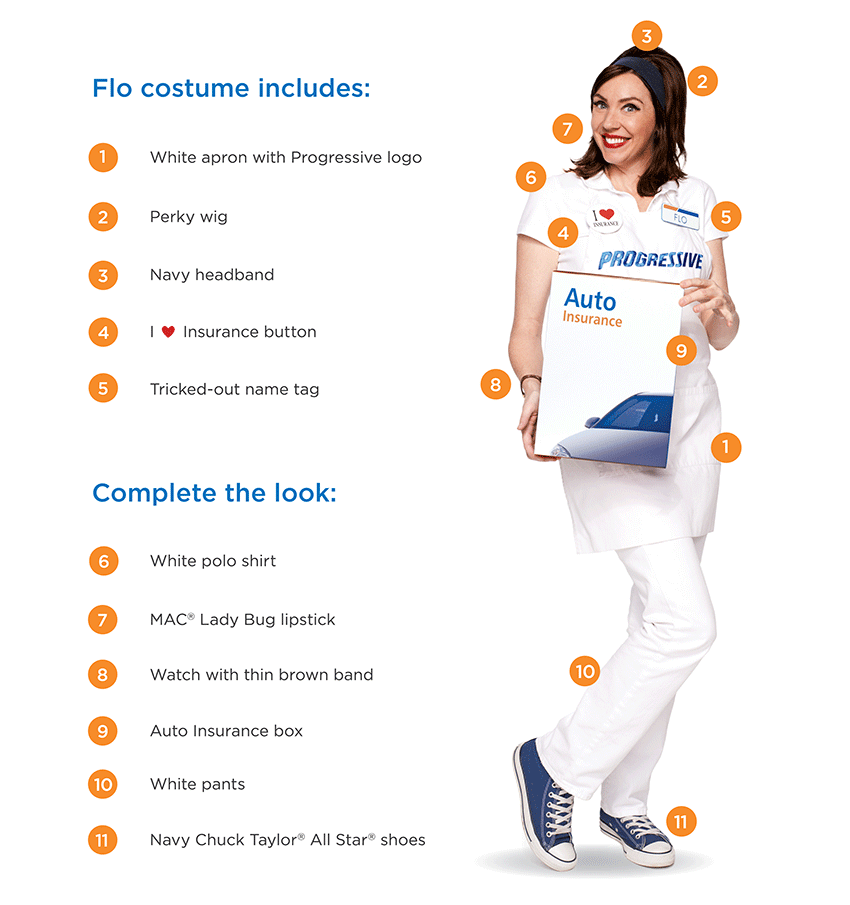

You know there’s something uncanny going on in American culture when people start donning Halloween costumes inspired by a popular figure. Progressive sells costume kits and doles out advice to Dress Like Flo, and people like to do so, if their imaginary spokesman’s (currently) 5.4 million facebook fans are any indication. Flo is everywhere, partly because we have absorbed her into our cultural personality. Flo is us and we are Flo.

There’s something about Flo that is appealing to the American masses. She never stops smiling and has all the affectation of an earnest clown, coupled with her mission to “protect” (as all insurance promises), so it’s hard not to like her. It could be her appearance that makes her almost “one of us” — the young “working mother” that she appears to be, working hard at the sell, always a true believer in her employer, because it allows her to play caregiver. Like a peppy Maytag Man or Verizon installation man (“Can you hear me now?”), she’s a model worker in some ways — an embodiment of the indefatigable zest the company wants to portray. But her apron is a sign of domesticity as much as it is of her job as insurance seller. And what’s uncanny about her it’s not just Flo’s almost inhumanly joyful personality, but her never-changing appearance. She IS the white apron uniform. She IS the haircut and name badge and lipstick-encircled teeth. It’s an infinitely reproducible look (in costume for both the actress on the commercial and for anyone at the Halloween party).

The television commercials that Progressive produce are quite well done and fully aware of Flo’s status as advertising icon. They are often self-reflexive in a way that incorporates elements of the uncanny. Take the “Superhouse” ad, for instance.

This commercial is more fantasy than message, depending almost entirely on its audience’s previously held knowledge about Flo and the whole oeuvre of Progressive insurance advertising. history. And it is in the strange familiarity of the imagery and the narrative logic of the fantastic that the characteristics of the uncanny begin to unsettle the husband on the sofa (the only character that does not change throughout), who ostensibly stands in for the spectator.

What makes this ad a vehicle of the popular uncanny?

First, the narration literally IS “progressive”: it displays the progressive transformation of a domestic space (the stereotypical family home) into the imaginary world of a Progressive insurance company — by stages, the home comes to resemble the stagey white and abstract set of the Progressive ads: Flo’s lair, if you will. It also displays an erasure of any individuality or personality that might have been resident in the home (though as I’ve said, that home is inherently a template, a stereotype, to begin with). Employing the structure of the Fantastic, the ad is literalizing the figurative , and we are asked to understand what we have just seen through the final metaphor, expressed by an unseen narrator at the very end: “The Name Your Price tool…making your world a little more Progressive.”

So what the commercial is doing is aligning “your world” with Progressive insurance, but we are only shown referents to various tropes in other Progressive commercials. Everything is “strangely familiar” but never quite stable in its reference: Flo is NOT in the ad. She is a ghost that possesses the mother figure, as she mixes her frosting. In cut after cut the uncanny magic of cinematic editing transforms her into Flo’s doppelganger. The walls in these shots become more and more like the set of the Progressive ads, until we get literal indicators (the housewife’s apron bears a logo, the boxed insurance “packages” have replaced books and other items on the shelves, and the “Check Out” sign hangs behind the housewife-turned-Flo-Clone, and in the end two minor characters from older Progressive ads suddenly appear on the couch to make a joke). Step by step, the “progressive” accumulation of signs of the company take over the domestic space…and it is this creeping sense of being taken over (as if buried alive) by the advertising that may trigger a sensation of the uncanny in the viewer.

Ostensibly, this narrative plays out in the mind of the man on the couch, fantasizing over his laptop. This is indicated by his frequent looks up toward the ceiling, the moments of silence during the ad when he seems to not respond or pay attention directly to his wife’s dialogue, etc.

But if we scrutinize the details in the advertisement, the male fantasy becomes even more disturbing. Why does the child on the couch, too, transform into a Flo? And why do the women in this ad seem to be clueless about their own transformation? To the latter point, it would seem they are objects of desire in the husband’s viewpoint — transformed from the subjects of familial love into objects of commerce and exchange, potentially of a sexual nature. How so? A Freudian might point to the housewife’s actions: “mixing the batter” is a metaphor for a sexual act, and the “name your price” line as it is delivered (“I’m looking at it right now”) is a bit of an innuendo for a sexual proposition. This subtle message is reinforced because the result is the figuration of a “baby Flo” — the child on the couch, a genetically-determined Flo, the result of sexual union between the unchanging man on the sofa and the Flo clone mixing her batter.

While a Freudian interpretation like the one above may be a bit laughable, the ad does seem to be entirely involved in “reproduction” in that it is literally engaged in reproducing the memory of earlier ads in the home, and in the viewer’s memory of Progressive advertising. One probably doesn’t normally think of the Flo icon as a sex object (i.e., she is a salesperson figure, not a supermodel selling beer), but every fictional ad is an expression of wish fulfillment. The wish expressed here is a little obscure — if it is male desire, then it mingles sexual longing with a desire for transformation of the domestic sphere into something more like…a workplace. An unconscious recognition of this occurs when the two male characters (who play “competitors” from other insurance carriers) appear on the sofa as if they too have moved in — and immediately ask about the bedroom (“the guest room situation”).

The sexual messages at work here play out at the same time as a domestic familial space is transformed into a commercialized insurance workplace. What underlies it all is not so much sex as familial ideology: a male fantasy about the ideal sexual division of labor. The husband is at leisure, fantasizing on the couch. The mother is essentially working in the kitchen throughout, “serving” her family’s needs. The child is passive and behaved in its unmoving silence. The unique elements of individual personality, familial love relations and female subjectivity undergo erasure, replaced by the generic world of the insurance company.

So of course the commercial cannot be entirely serious or realistic. It remains disturbing, uncanny, unsettling…all because it is not human at all. To me, this ad is a representation of virtually all advertising and how it progressively saturates so deeply into our everyday lives that we cannot distinguish between fantasy and reality, sign and symbol. This intellectual uncertainty, mixed in with unconscious and emotion-laden desire, as well as gendered fantasies of domesticity, stirs up the batter to produce very Unheimlich results.

These issues do appear in other advertisements as well. I’ll conclude by simply sharing the Progressive “Hand Puppet” commercial, in which a woman schizophrenically splits into housewife and Flo puppet, which I think speaks for itself:

Recent Comments