While doing a little holiday shopping last Fall (on the occult-sounding ritual known as “Black Friday”), I spotted a bargain and caved in, buying something for myself. I purchased a gigantic external hard drive — with a Terabyte of space — to archive my files: a Maxtor OneTouch 4. Imagine my surprise when I opened the box and discovered that every item in the box came in a baggie that was sealed with a sticker that read, simply, “Save your life.”

For a moment — just a moment — I was struck with a sense of the uncanny. It felt like a message from beyond, portending doom. Or just a really ominous fortune cookie. The syntax and rhetorical stance of the slogan didn’t help. The surprise of being directly addressed by the unexpected stickers was felt as commanding to me; the urgency of the claim sounded more like “Run for your life!” than “Save it.”

The feeling of being caught off-guard like this, of encountering presence where one expects absence, is entirely uncanny.

Usually when I buy a product, I’ve been so saturated by packaging and advertising slogans beforehand that things like this don’t catch me off-guard. This was more like a Jack-in-the-Box of advertising. I decided to look into this campaign a little bit.

In their brochure, Maxtor makes the pitch for their product in a language that feels like a thinly veiled death threat:

Save your life.

We are nothing more than the sum of our experiences. The pictures we take. The music we love. The work we do. This is how we are cataloging our existence. These are our lives. Everything we capture, share and create adds to us. And anything lost takes a piece of us with it.

Forever.

And forever means forever.

If that doesn’t sound like a death threat to you, try reading it again, out loud, using the voice of one of the cast members from The Sopranos, and you’ll see what I mean.

“Save your life” is a brilliant marketing slogan for a manufacturer of hard drives who wants you to buy their “peripheral” so that it becomes “central” to your computing life. Obviously, backing up your work to a storage archive is a superlative idea, especially if you are creating documents that need to establish evidence of some kind. Since buying this drive, I have come to rely on it to archive my files (including the very document I am typing right now!), so I don’t mean to suggest that the product is not a life-saver. But in the bigger picture, one has to ask: do the trace recordings of your experience — embedded in such things as photos and audio files and to do lists — really constitute “your life”?

Of course we say things like this casually all the time. I know several people who call their cell phones their “lives” since it contains information and data crucial to their jobs and daily routines. A “life” — when used in a generalized context, like Maxtor’s slogan — could mean a “social” life. Or a “family” life. Or a “meaningful” life. Or a “spiritual” life.

But “Save your life”? Maxtor’s advertising campaign is a cautionary phrase; their substitution of a period for an exclamation mark at its terminus does not fool me. The company is saying that my life is at risk. The obsidian tombstone-like appearance of the product — a Kubrickean black obelisk — reminds me of the ticking clock. My data is going to die if I don’t act fast.

The implication, of course, is that you — the consumer — can “lose” your life if you don’t back it up. This is the threat of document-centered culture. But on a psychosocial level, the implication is also that you are always already dying (or perhaps your social/family/spiritual life is on the wane) — and that, if you’re willing to pay the right price, consumer goods can save you.

The implication, of course, is that you — the consumer — can “lose” your life if you don’t back it up. This is the threat of document-centered culture. But on a psychosocial level, the implication is also that you are always already dying (or perhaps your social/family/spiritual life is on the wane) — and that, if you’re willing to pay the right price, consumer goods can save you.

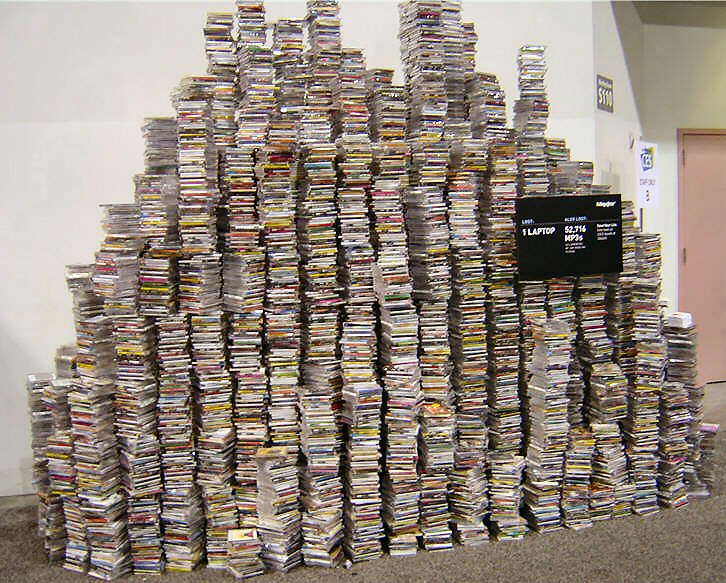

Indeed, we accumulate so much anymore that it is downright scary. We can end up “spending” our lives saving things so obsessively. The bloggers at A Wider Net noticed that, as part of their ad campaign, Maxtor set up displays in airports that strongly visualize how much of our files we put on our computers. Here’s the monstrous music display that concretely represents the number of CDs you can store on a typical laptop:

We answer the threat of death — or massive loss — with the uncanny, and often respond in irrational ways. Sometimes it is made manifest in the compulsion to repeat. At other times is felt in the urgency to hold on and collect objects in a shopping spree. With our data — our proof of life in postmodern culture — we “save” it by “backing up.” But with many of us, it goes beyond merely copying and archiving a secondary file. It is “saving” through “mirroring” a hard drive in its entirety. And subsequently cloning your life as it appears in data. It is the first step into obsessive “lifelogging.”

Black boxes indeed.

Your post made me run Time Machine on my Mac. Just thought I’d share.

To that effect, I have an Apple Time Capsule. I backup wirelessly now using the same device that keeps me from being tethered to a desk to use the internet. Time Capsule has the usual Apple design features–lovely glossy white case, an appealing flat square shape sporting a shiny silver logo on the top. (The only design flaw, as far as I’m concerned, is the seemingly huge green status light on the front of the thing.) Not as ominous as the obelisk you have (LOVE the Kubrick reference), but maybe that’s because Apple designed it… Someone I know and love called it an arctic pancake.