“Dreamland” is an amazing concept for an amusement park attraction based on literal interpretations of Freud’s theories.

I’m learning about this from Zoe Beloff‘s exhibition at Coney Island museum (running till July 2010): The Coney Island Amateur Psychoanalytic Society and Its Circle, 1926-72. I’m ordering the book that covers the history of this fascinating group, and I can’t wait to spend time with it. For now, I just want to share coverage of the exhibit in an article, “The Case of Sigmund F. and Coney I.” from The New York Times, which generously includes a slide show of images from the exhibit.

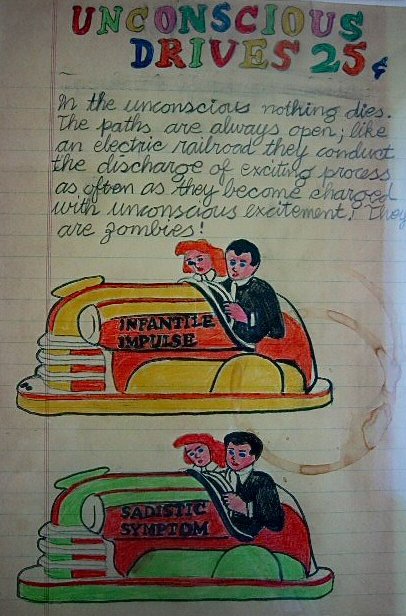

Albert Grass led the Amateur Psychoanalytic group, who proposed to restore and renovate ther “Dreamland” park area as “the first amusement park ever devoted to the elucidation of dreams in accordance with the discoveries of Doctor Sigmund Freud M.D.” Grass’ sketches of the rides and attractions of the id are compelling works of art in themselves, such as the autonomous bumper cars that function as “unconscious drives — 25 cents!” (image at the top of this post is from good coverage of the exhibit at Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York blog…which also features an interview with Beloff). The textual notes (“In the unconscious nothing dies…They (the drives) are zombies!”) are at once an accurate description of Freudian thought and an unsettling literalization of anxiety and desire.

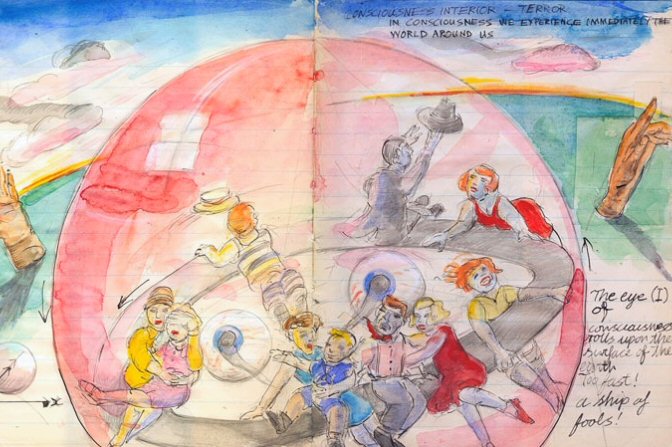

As the museum’s press release for the exhibit explains, Grass’s sketches and plans included “a working architectural model consisting of a series of pavilions (The Unconscious, Dream Works, Consciousness, The Censor), linked by a miniature locomotive (The Train of Thought)…integrat[ing the Group’s]intellectual interests into its surroundings, in ways both serious and amusing.”

How uncanny it would be to literally ride the unconscious and traipse along the pathways of the Dream Works. And I can only guess the horror of “The Censor” pavilion. By making the “figurative” elements of psychoanalytic theory “real,” the park attraction would have constituted an amazing fantasy adventure, but one that would resist the suspension of disbelief in that it would always already be a sort of projection of a conscious rationality in its very design. I suppose, there is a degree to which this is less an instance of the uncanny “confusion” between a symbol and what it symbolizes, and more a projection of the omnipotence of Freudian thought. Or, conversely, an artistic comment on Freudian thought as, itself, fantasy.