I was excited to see that Dan Coxon and Richard V. Hirst recently won the British Fantasy Award for “Best Non-Fiction” with last year’s important release from dead ink books, called WRITING THE UNCANNY: Essays on Crafting Strange Fiction.

Coxon and Hirst’s book is an excellent anthology of mostly-UK writers sharing their strategies for writing on the dark side, but what makes it so strong is that its assembled authors avoid the impulse to reduce its advice to any formulaic “how-to” about tapping into the uncanny; these fiction writers seem to know their theory, and respectfully work around the central problem of constructing the “strangely familiar”: that the uncanny (like humor) is one of those things you can’t quite express through words — it resists over-simplification — but it is embedded in the experience of literary and artistic representation.

Indeed, some of the authors in Writing the Uncanny tackle the way dark humor and the uncanny seem to overlap, and I enjoyed the contribution “Finding the Comedy in the Blatantly Unfunny” by Robert Shearman. It is one of the best writer’s memoirs I’ve read in quite some time. His deconstruction of a Roald Dahl short story that people frequently overlook, “Pig,” is one of the best pieces I’ve seen on Dahl, and celebrates the unexpected gore of that YA (?) story, grapples with its confounding ending, which leaves the reader stunned with a “Wait, what is the meaning of this?” kind of ending — a withheld reassurance, or as Shearman puts it, a “sense that the comedian isn’t on your side.” This essay reminds us that not everything is explicable and that sometimes the most chilling work by a writer is inexplicable.

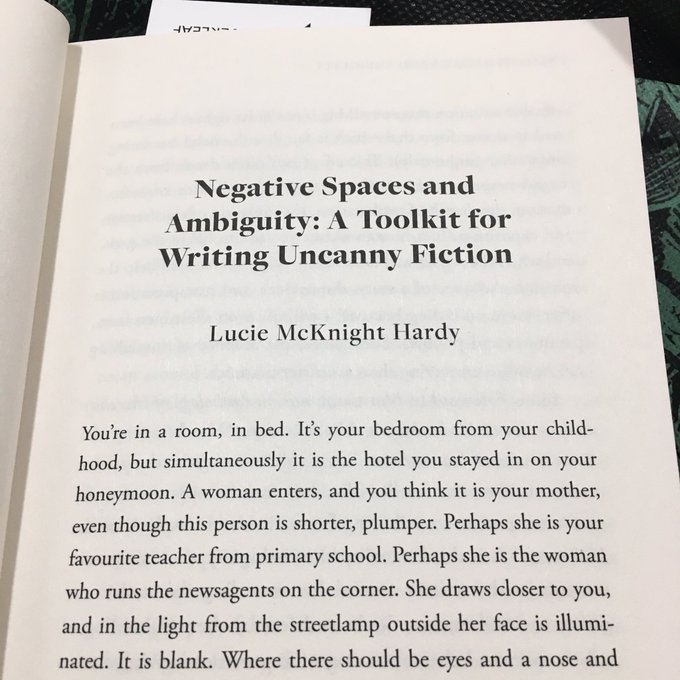

Similarly, Lucie McKnight Hardy’s essay, “Negative Spaces and Ambiguity: A Toolkit for Writing Uncanny Fiction” — certainly the best instructional essay in the book, and required reading for all would-be horror writers — explores how authors might construct and work around gaps in their work, leaving room for readers to imagine and therefore dread the worst things in the negative space of their stories. The places where nothing is happening in a story (where perhaps it ought to) often draws our attention the most, and Hardy knows how to exploit that.

Mandatory reading for horror writers — the brilliant opening essay in Writing the Uncanny by @LMcKnightHardy — get the whole thing from @DeadInkBooks @DanCoxonAuthor @vivmondo pic.twitter.com/Rh7guoEWbY

— Michael Arnzen (@MikeArnzen) July 23, 2022

Several essays in the book explore haunting, with Catriona Ward smartly exploring “Housing Ghosts in Fiction” and Jenn Ashworth focusing on ghosts as characters. As with Ward’s piece, place is prominent in the book, and a section on “Land and Lore” offers a wealth of expertise. Well-known expert on the uncanny, Nicholas Royle, contributes a piece called “Beach Reading,” which artfully unpacks the weirdness of tales of oceanic uncanniness and the liminal spaces where waves meet sand.

Authors and thinkers too get special treatment. In his essay, “Personal Experience in the Uncanny,” Alison Moore looks at the writing of Shirley Jackson, who is a master of the domestic uncanny. Jeremy Dyson puts a spotlight on the disturbing psychological fiction of Robert Aickman which deserve more study. And of course Sigmund Freud is haunting the whole anthology, but pops his head out most prominently at the end in Timothy J. Jarvis’ closing essay, “You Must All Be Very Worried,” which enlightens Freud’s “Das Unheimliche” and it’s treatment of ETA Hoffman’s classic “The Sandman.”

Writing the Uncanny is commendable for both its advice for writers interested in the darker side of psychology, and also its exploration of theories of the unhemilich from a variety of thoughtful perspectives. It is this balance of theory and praxis which make it an excellent read, and there are plenty of entertaining moments too, (like Rowan Hisayo Buchanan’s “All You Have to do is Die,” which almosts presents itself like an orientation course in how to die your best death as a ghost). If there’s any weakness, it might be that the book might be a little too focused on UK writing, but then again, that may be its strength, and it is natural given the publisher is sponsored by the British Arts Council and the majority of contributors hail from the British Isles. Yet the subject matter transcends nationality, and there are international authors included and discussed.

In my opinion, the universality of this subject is made evident by the hidden treasure we are gifted with in the back of the book: an excellent bibliography in the appendix of FIFTY uncanny novels and ONE HUNDRED uncanny short stories. If one wishes to truly learn the craft of the uncanny — or to experience it deeply time and time again — reading this book and all of these titles in the back of the book (alongside Comma Press’ The New Uncanny (2018)) would certainly be the best way to learn, get inspired, and be…chilled to the bone.