In his essay on “The Uncanny,” Sigmund Freud writes:

…an uncanny effect is often and easily produced when the distinction between imagination and reality is effaced, as when something that we have hitherto regarded as imaginary appears before us in reality, or when a symbol takes over the full functions of the thing it symbolizes, and so on.

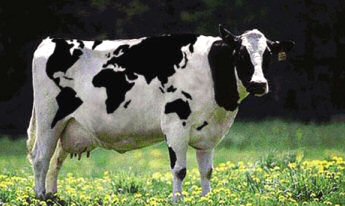

Freud’s notion about the uncanny power of the symbol overtaking its referent is everywhere evident in pop culture and vox populi is doing a great job documenting our culture’s fascination with the popular uncanny on the internet. Indeed, there are so many websites that function as virtual “curiosity shoppes” online that it would be impossible to gather them all here. From the most popular weblogs (like Boing Boing) or magazines (like Wired) that seem fixated on uncanny and fantastic gadgets — and whose very names and logos imbue a sort of living energy to symbolic language — to the everyday blogs on myspace and elsewhere where people routinely post the photoshopped or animated images they find in some public gallery, or on youtube where homemade animations and films are everywhere, our human fascination with the uncanny saturates the online environment. And this makes sense, because personal computers excel at animating the inanimate and connect with the “worldwide” culture in its metaphoric web.

Along these lines, I recently found a a provocative weblog called Next Nature, which I adore. Next Nature is documenting Freud’s “uncanny effect” of the autonomous symbol on a cultural scale by calling attention to phenomena where “culture becomes nature” (and vice versa). It is not “environmentalist” in the traditional sense — its definition of “nature” is more akin to AdBusters’ emphasis on the “mental environment” or what we might term our cultural ecology. The symbols that we create and bring to life in our culture not only have an impact on our environment, they become a living part of it. As Next Nature’s authors say in their FAQ, “Old nature, in the sense of trees, plants, animals, atoms, or climate, is getting increasingly controlled and governed by man. It has turned into a cultural category. At the same time, products of culture, which we used to be in control of man, tend to outgrow us and become autonomous.” (Read Koert Van Mensvoort’s essay, “Real Nature is Not Green” — or explore his professional website — for extensions of the logic behind this).

It’s a fun and fascinating site, posting everything from articles on postmodern theory to offbeat photoshopped (or is it?) images of the strange, like that World Cow image above (which is disturbing not only because it captures the essence of the quote by Freud cited above, but also because it seems to hyperrealize the idea that we are consuming our planet). I especially enjoyed discovering their pointer to Metalosis Maligna (also on YouTube): a mockumentary about an imaginary disease that occurs not to our bodies, but to the implants and other cyborg technologies we put into our bodies, resulting in transhuman horrors. I recommend browsing through their categorical tags, which reads like a catalog of the uncanny, with keywords like anthropomorphobia or toys are us. If you are interested in the academics of all this, check out their theory section, where you’ll find profundity like this idea from Eric Hoffer:

You dehumanize a man as much by returning him to nature – by making him one with rocks, vegetation, and animals – as by turning him into a machine.

Both the natural and the mechanical are the opposite of that which is uniquely human.

So often — perhaps because the idea emerged along with modernist Industrialism — we align the uncanny with the mechanical or “unnatural,” rather than the natural. The uncanny is often about the confusing loss of boundaries between the two, stunning us by calling our assumptions about what constitutes the natural and the human into question. I find Hoffer’s notion that the ‘natural’ is the antithesis of the ‘human’ a very counter-intuitive yet nonetheless extremely profound, notion.

Mensvoort and others associated with the Next Nature website have produced an image and theory-laden paperback book worth seeking out.

Dear Michael,

I published a book that puts the uncanny at the center of its argument that in order to have ecology, we must give up Nature. You might be interested in it (see blog).

Slavoj Zizek talks about it on YouTube–i sent him a copy last June.

I’m writing abook called The Ecological Thought, which goes even further into these issues.

Yours sincerely,

Timothy Morton