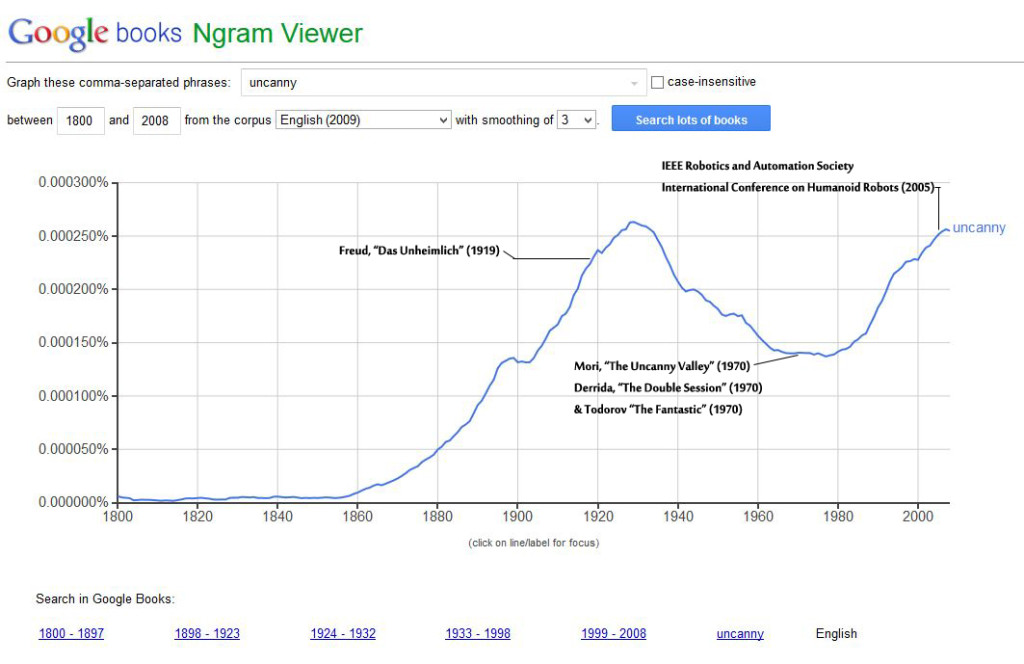

Although there is some wise debate about the reliability of Google NGrams as statistical proof, it is still interesting to see the way the term “uncanny” has come into — and gone out of — fashion over the years… Here’s how google NGram tracks the appearance of the term “uncanny” in all books between 1800 and 2008:

One can’t help but see the two high points of the term — cresting in 1928 and almost at the very same point in 2008 (though I suspect the chart would be at an all time high if it reflected today’s rate in 2015). What does this tell us? What speculations can we make about this?

Well, as much as it might mean nothing whatsoever, the chart does make us wonder about correlations. And perhaps it does provide some indication of the circulation of the term in common parlance, which is pertinent to my study of the popular uncanny.

I would suggest that the term is a meme that circulates more frequently during times when a culture is unconsciously registering a “return of the repressed.” In other words, it’s reasonable to argue that the chart above points to times over the century when writers were grappling with a feeling of unease, deja vu or strange familiarity — since they were using the term to describe this phenomena more or less often in their writing. One could point to cultural tensions like, say, World Wars or economic recessions and depressions and suggest these are historically linked to such anxiety. But for the time being, I am looking at this chart and considering how it reflects the term’s usage as a critical apparatus. If we label the chart with a few of the key publications related to the phenomenology of the Uncanny, we can see their relationship to these trends fairly easily:

It seems fairly clear to me that Freud’s touchstone essay on “Das Unheimlich,” published in 1919 (responding to Jentsch’s 1906 essay on the topic) was as much a product of its time as it was a contributor to it. I want to speculate that Freud’s discussion of the term as a critical concept as much as a word to describe a feeling led to coining the term as a “buzz” word, as well. So it makes sense that the word would rise in popularity for the decade or so following the publication of “Das Unheimlich,” reaching its high point in usage in the period between 1920 and 1940 — even if this was not necessarily Freud’s most notable article during the period (which may have been”Beyond the Pleasure Principle” — with its uncanny-related concepts of the Death Drive and “repetition compulsion” as it related to war veterans). Of course, Freud alone does not have ownership of the term. I believe popular/pulp fiction also contributed to its popularity during this period, with “uncanny” tales being labeled as such. And as the term becomes more familiar, more domesticated, more marketed, it begins to fall out of fashion.

So what brings us to the “second wave”? Anneleen Masschelein, in her book The Unconcept, has quite excellently accounted for the “canonization” of the term Uncanny by the “uncanny critics” of literary psychoanalysis in the 1980s and 90s — a historical argument that certainly is supported by this second wave of the uncanny in the NGram chart. Masschelein specifically points to 1970 as a turning point, when deconstructionists like Derrida, Todorov and Cixous were writing about the concept in relation to psychoanalysis and literature, at the same time as Lacanian critics were discussing the concept in their journals, producing a watershed of criticism among deconstructionists like J. Hillis Miller, Jonathan Culler and others who employed the term in their writing. Thus, the surge evident in the chart between 1980 and 2000 really echoes the rise of the term in literary and cultural theory, as much as popular parlance.

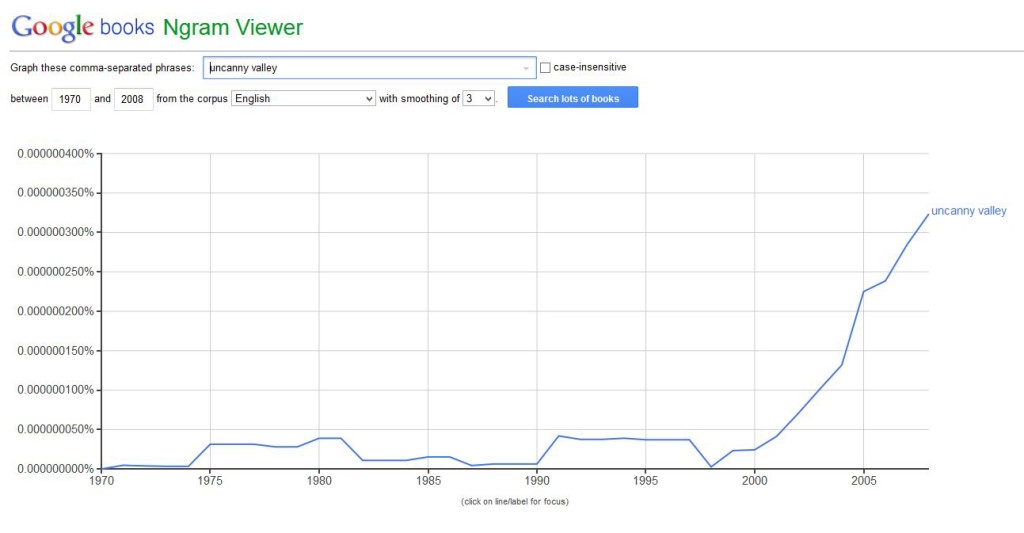

Although not a party to such matters, Masahiro Mori’s concept of “the uncanny valley,” notably, was ALSO first published in this “turning point” year of 1970 (which ironically falls in the “valley” of this chart). But it was not really until a 2005 conference on Robotics that Mori’s famous phrase began circulating broadly in works by those interested in robot and android science, leading to the second high point of 2008, with no sign of decline, given its popular appearance in circles across the internet today, when popular culture has picked up on the phrase and we now see it more commoonly in gaming circles, in Science Fiction, in art theses, and even on TV shows like 30 Rock. Here’s a close up on the more-specific phrase, “uncanny valley,” as it has circulated since Mori’s publication of the concept in 1970, showing not only the rise in 2005 related to the robotics conference, but a definite leap in the years following 2005 up leading toward the unchartable figures that no doubt are even higher today.

In some ways this ascent of “uncanny valley” may soon be the dominant understanding of the uncanny, replacing the unheimlich of Freud and the deconstructionists, though Mori is certainly in some ways informed by Freud, even if the phrase subordinates (or represses?) his original theory.

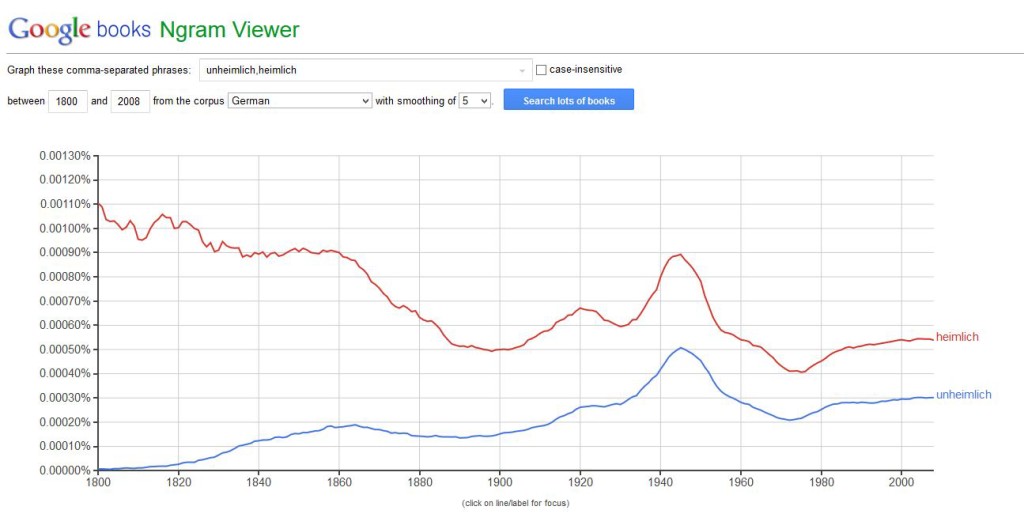

And though all of this charting and speculation is somewhat frivolous, in reflecting on these matters, I’m reminded of Freud’s etymological discussion of the terminology for the uncanny itself, and how in part one of his essay, he argues that the term “heimlich” (familiar) over time evolved into the “unheimlich” (strange) — leading to his great line about how “the un- is the token of repression.” So for kicks, I thought I’d pop both these words into Google’s NGram chart using German books to see how they compared:

To my amazement: the terms unheimlich and heimlich almost converge in 1900 and set into a pattern that — dare I say it — “eerily” follows a parallel moevement thereafter, like an uncanny double. The more things change, the more they stay the same.