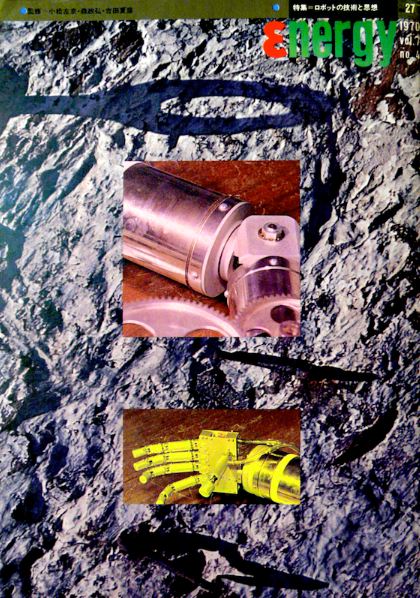

I like to think I’m good at keeping up with research on the Uncanny, but somehow I missed an important event this June: IEEE Spectrum published the first complete English translation of Masahiro Mori’s highly influential article on “The Uncanny Valley” (originally published in what they call “an obscure Japanese journal called Energy in 1970,” and circulating in the robotics community and popular culture in only partial form. This current translation, by robotics experts Karl F. MacDorman and Norri Kageki, has been authorized and reviewed by Mori himself.

You can read the complete “The Uncanny Valley” by Masahiro Mori online here: [HTML | PDF]

Here are my initial notes as I read Mori’s article in full:

+ Movement has a more significant role in the theory than I think people who work with this theory really recognize. In the introduction to the essay, he makes the stunningly simple point that “many people struggle through life by persistently pushing without understanding the effectiveness of pulling back. That is why people usually are puzzled when faced with some phenomenon that this function (an algebraic equation for “monotonically increasing” or accelerating forward movement) cannot represent.” In other words, the “uncanny” is referring to the “puzzling” phenomenology of feeling “pulled back” from a situation where we expect forward motion. I like this, as it gives me another way of thinking of the “double-take” that I associate often with das Unheimliche.

+ Death is conceived as the end of movement. In the end of Mori’s article, he associates this “pulling back” with death itself: “into the still valley of the corpse and not the valley animated by the living dead.” He even goes so far as to theorize that the repulsion of the uncanny is “an integral part of our instinct for self preservation…that protects us from proximal, rather than distal, sources of danger.”

+ One shouldn’t forget that the “Valley” is always symbolic, a metaphor for a sensation. I am struck by Mori’s reliance on metaphors throughout the article…and reminded that the very idea of the “valley” is really a geographic analogy for a dip in his infamous graph. The “sinking feeling” one associates with a dip in the road or the sudden plunge of a roller coaster might be just the right sensation he is after in this. He directly compare the “uncanny valley” to an “approach” of a hiker climbing a mountain who must sometimes traverse “intervening hills and valleys”. Mori thesis statement encapsulates this in a nutshell: “I have noticed that in climbing toward the goal of making robots appear like a human, our affinity for them increases until we come to a valley which I call the ‘uncanny valley'” (emphasis added).

+ Aesthetics and childhood factor into this theory as much as Freud’s. Mori notes that the trend for designing robots that look human really started to pick up in toy robots, rather than in the (perhaps more frightening) factory robots that replace human workers. Obviously, the aesthetics mean more than the instrumental functions of these toys, which are like Freud’s puppets or uncanny dolls. Interestingly, Mori writes that “Children seem to feel deeply connected to these toy robots” and puts them on the top of the first “hill” before the chart dips down toward the deadly “uncanny” valley. What I would note here is that Freud conceives of the uncanny as a return of a repressed or infantile belief that such objects as toys and dolls have life all their own. After the dip of the “uncanny valley” Mori returns to toys by citing the “Bunraku Puppet” as an example. So perhaps Mori’s chart actually follows Freud’s logic to the letter — the dip or valley is the return of the repressed, insofar as it follows the same chronological structure of childhood belief, followed by its later return in adulthood.

+ The focus on hands, rather than faces or heads, is intriguing. Mori focuses on the robotic hand as his primary example: “we could be startled during a handshake by its limp boneless grip together with its texture and coldness…the hand becomes uncanny.” Later Mori develops this by describing a robotic hand as prosthetic limb: “…if someone wearing the hand in a dark place shook a woman’s hand with it, the woman would assuredly shriek.” Note that Sigmund Freud’s original article on the Uncanny (1919) features examples of dismembered limbs and hands that “move of their own accord” as well. The hand is a particularly loaded body part: it is a way we communicate by sign, it is one of the ways that “human” is separated from other members of the “animal” kingdom (by opposable thumb), and it is something we look to as a signifier of intention. Language is rooted in the hand. And it is a metaphor for control (i.e. having everything “in hand”). The Uncanny, as I think of it, is often a phenomena that disorients us and — often as if by an “unseen hand” — reminds us of our lack of mastery in a situation where we normally would presume we had it.

+ As Mori progresses to unpack his theory, the more his descriptions of prosthetic devices become akin to horror fiction. Indeed, he makes the comparison himself: “Imagine a craftsman being awakened suddenly in the dead of night. He searches downstairs for something among a crowd of mannequins in his workshop. If the mannequins started to move, it would be like a horror story.” Indeed, the surprising movement where one expected stillness from the inorganic objects would be startling and felt as uncanny. It would not merely be identity confusion. It would feel as if the robots were attacking. The boundaries between “story” and reality would become blurry. Science would become science fiction “made real.”

I’m sure I’ll return to this article again in the future. For now, of equal interest is Kageki’s contemporary interview with Mori himself also published in the 2012 issue of Spectrum, asking him to look back on the theory. My favorite moment is the when Kageki asks him, “Do you think there are robots that have crossed the uncanny valley?” Mori suggests that the HRP-4C robot is one of them. But then he doubles back and says “on second thought, it may still have a bit of eeriness in it.”

The HRP-4C is a dancing robot, among other things (see the HRP-4C YouTube channel). You can see it in action and judge its uncanny nature for yourself.

I am so thankful to Mori and the translators for re-releasing this version of the article in English for scholarly review. It has been relatively frustrating to see the essay referred to so often in both the design and gaming community — as well as in scholarly circles — without having access to the complete source, and now that it is available I hope others will continue to test and explore its legitimacy as a way of thinking about horror aesthetics and anthropological design.

I’ve written often about the Uncanny Valley elsewhere on this blog.

It’s a fantastic resource for me to have the new translation available – and just at the right time when I’m writing up the results of my years of research into this area. I’ve been reflecting on how my approach would have been different if I’d been starting with the current translation rather than the one available in 2005 – not very, I don’t think. My specialism has been on faces and I still feel they’re particularly salient even if hands and limbs do gain a lot of attention in the new translation. The horror elements certainly chime well with what I’ve been doing!

Thank you for finding the magazine cover, by the way – I’ve never seen that. Odd (to me at least) to think of this as a psychical publication. I’ve only ever read it online…

Thank you so much Stephanie, for your comment and for the kind words on your fantastic resource at: http://www.scoop.it/t/uncanny-valley I think we both agree that it is not only great to have access to the full original document in translation but also a testimony to how important it is to refer to primary sources and not second or thirdhand documents in scholarly research. The release of this article is as important, I think, in uncanny scholarship as the translation of Jentsch’s piece on the Uncanny that inspired Freud’s essay a century ago — which the journal Angelaki released just a decade ago http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09697259708571910 ). Looking forward to seeing how your work progresses.