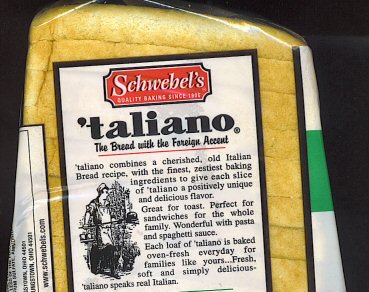

Obviously, no one believes bread can talk. But Schwebel’s ‘taliano — “The Bread with the Foreign Accent” — would like us to believe its Italian bread has an identity so Italian that it can speak to us.

I used this example in my recent lecture at the Alpha Science Fiction & Fantasy Workshop for Young Writers, arguing that fictional “fantasy” is everywhere around us — and that the Uncanny is the genre of our everyday lives, lurking in messages like this that we see so often in popular culture that we’ve become immune to them.

Part of my reason for bringing this up was to suggest that creative writers should be on the lookout for messages like these, because everyday life is ripe with concepts that can prompt ideas for fantastic tales. Another reason I raised this matter was to discuss the differences between fantasies in advertising and fantasies in stories: and the difference, we agreed, was that stories provide meaning to our lives, whereas consumable goods simply pretend to do more than they really can, in a quest for profit and attention. They use not only consumer fantasy, but also tropes of the literary fantastic and the uncanny to persuade us…into not only making a purchase, but also to develop a sort of brand loyalty. They accomplish this by anthropomorphizing their objects and framing them as living creatures just like us, with personality and voice.

We don’t believe it. We have, in Freud’s words, “surmounted” our infantile belief in the “omnipotence of thoughts” — the anthropomorphic and animistic fantasy that would allow something like dough to be more like man than flour and water. But we suspend disbelief anyway, because the regressive “inner child” still wants to believe and the unconscious will believe whatever it wants to in a quest to consume.

I didn’t go too far into psychoanalysis at the Alpha Writer’s Workshop. But to stimulate story ideas with the group, I asked the students: “What if bread could talk to us? What do you think it would say?”

They laughed, and started saying things like “Don’t eat me!” and “Oh no…not the toaster!” in funny accents.

Exactly. The back of the bread package features a nostalgic-looking image of an old style baker shoving a loaf into the fiery oven. Does this not take on a creepy and chilling meaning, if we are to suspend our disbelief in bread that talks in a foreign accent? My point is ludicrous, of course, but this is because the message is mixed: they seem to be saying, “our product is just like people — so let’s throw it in the oven.” How are we to make sense of such horrifying contradictions?

One answer lies in the psychology of projection. If we were to entertain the childhood fantasy that these products really are living creatures, with human abilities, then our own desire to consume logically becomes mirrored back at us: we will fear that what we want to eat might also want to eat us. Consumption is inherently aggressive. (My point is related to object-relations theory, especially Melanie Klein’s theory of the “bad breast”). Thus, we must be reminded — with images of ovens and kitchens that appeal to our adult sense of mastery and civilization — that this really is just dough we’re talking about, after all.

Even so, nothin’ says lovin’ like…dough.

[See the disturbingly brilliant “Yeast Infection” exhibition to see how various artists have explored the Doughboy’s dark side!]