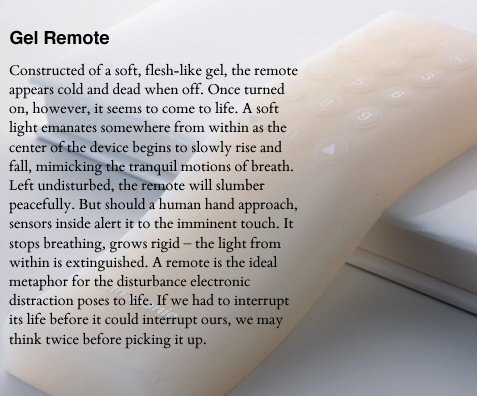

Adbusters # 78 asks “What if design stood up for itself? What if instead of bowing immediately to our demands, design gently pushed back?” In the “Psychodesign” slideshow (by Sarah Nardi), products like Panasonic Design Company‘s experimental “Gel Remote” (above) are framed as a political use of the uncanny, animating the inanimate icons of everyday life in order to challenge and subvert the objects that enable our sense of mastery and dominance over the environment:

Inert and lifeless, design is animated only through human use. It exists only by virtue of its functionality, possessing no reality independent of its purpose in our world. Would we think of it differently if it were alive?

What products designs like these are asking us to do is empathize with objects, which in my opinion (following Susan Verducci) can be a progressive and moral outcome of an imaginative representation of the uncanny in the arts.

But the “gel remote” got me thinking about the sensation of touch. The gel remote — and other forms of haptic technology/art/design — are inanimate objects that “touch back” when we touch them. So much of the theoretical work on the uncanny has been about the visual realm and other forms of representation; haptic technology and art is a new media form that projects a sort of tactile sensation of the uncanny, which in some ways is like a “return of the gaze” in the plane of the visual.

A little web research reveals the artistic history behind the remote and other objects of this ilk. It stems from Kenya Hara’s attempt to assemble a group of Japanese artists to design an object from everyday life that animated tactile perception. Japan Society cites him on the concept:

“The concept of ‘haptic,’…leads to the idea that we not only design form by creating a shape or an object, we also design how it feels. A human being is a bundle of delicate senses. Science doesn’t only help the evolution of materials and media, it also helps us understand the senses, where there may be hidden a whole new, undiscovered territory. . . ‘Haptic’ means another design attempt to expand the world atlas of senses.”

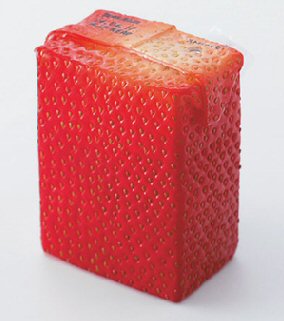

The Lighthouse art museum of Glasgow hosted this “haptic art” exhibition earlier this year, showing the Gel Remote along with a few other designs that I’d place in this category of the tactile uncanny, like Naoto Fukasawa‘s “Juice Skin”:

These examples of the repackaging of nature (a la Next Nature) are at once novel and attractive. A review by The Scotsman of the Haptic exhibition celebrates the mission in our audio-visual centered world to reawaken the senses of touch, but laments that samples of these art objects were rubbed smooth by passers-by.

We are both attracted to and repulsed by such objects.

A good starting point for explaining the feelings aroused by actually touching — rather than seeing — this sort of object might be this example from Jentsch’s essay on the Uncanny, which describes the “intellectual uncertainty” one has when one can’t tell what causes a “perceived movement”:

One can read now and then in old accounts of journeys that someone sat down in an ancient forest on a tree trunk and that, to the horror of the traveler, this trunk suddenly began to move and showed itself to be a giant snake…. As long as the doubt as to the nature of the perceived movement lasts, and with it the obscurity of its cause, a feeling of terror persists in the person concerned.

The terror he describes is triggered by sitting on an object that shows itself to actually be a subject. More than just the striking surprise of a statue that suddenly lights up with life, there is a moment of abjection on top of the terror caught up in touching what one assumed was “dead” material that surprisingly touches back with a “life” all its own. This sensation of touch literally “pushes our buttons” perhaps more forcefully than any other form of the uncanny. Haptic art/tech does not merely reawaken the sense of touch; it triggers a reflexive response that inherently asks us to rethink our assumptions about the environment.

It grows rigid when you get near it?

That’s one fancy dildo, guys.