Kudos to the fast food chain Burger King (and their marketing team, led by VP Fer Merchado), for making a bold step in addressing the special needs of people with hearing disabilities. To celebrate the most recent American Sign Language Day (on April 15th, 2016), they ran an advertising campaign that directly targeted the deaf, which included overhauling an entire restaurant in Washington DC, and replacing all lettering on their materials with symbols of hand-lettering in ASL sign. It also launched a viral marketing campaign featuring the heretofore silent King, who on video signs to the audience and invites viewers to create a new hand gesture for their Whopper sandwich — the “Whoppersign” — and to post a video of it online with the search tag “#whoppersign.”

The #whoppersign campaign is a wonderful advertising gambit with a fantastic aim: to respect and serve the hearing impaired community. You have to applaud Burger King for marshaling its chinadoll-faced mascot, King, to employ American Sign Language and turn to a higher social purpose. Check out the original video and its backstory, as recently published at AdWeek.

There’s good inside coverage of the King live from ASL Day (4/15/16) at the restaurant in Washington DC on YouTube. And of course, you should peruse the various video submissions for #whoppersign on twitter, all in ASL.

Mental Floss explains why this is progressive advertising: “It differs from many ad campaigns of this type, in that it’s not about a company giving something to a disadvantaged community, but about asking for their input on something. Also, the commercial spends time letting signers explain for themselves what they love about their language, which makes it a perfect contribution to the celebration of National ASL Day.” In other words, there is empowerment through self-expression here, where the consumers are entrusted and given power over the creative messaging.

It is wonderful to see a marginalized group served by the franchise and, I think — as one hearing-disabled writer has put it — it would really be great if this kind of appeal was a permanent, real fixture, especially if it were expanded to areas where there is a high demographic of deaf and hard of hearing populations.

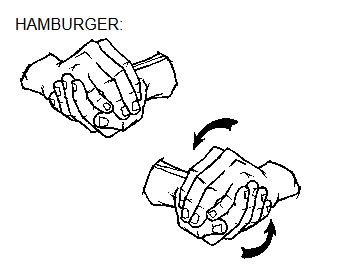

BK is making a step in the right direction, certainly, but if it weren’t for the warm embrace of the deaf community so far, one could just as easily see this as an exploitative publicity stunt. I prefer to give them the benefit of the doubt, because it does open up a dialogue with the hearing-disabled and it does show that BK is serious in their corporate commitment to diversity and inclusion. But of course it is also very much in their vested interest to not only appeal to a target audience by “speaking their language” in an effort to develop brand loyalty, but it is also crass commercialism to presume that their hamburger deserves something more than a trademark — its own word in the lexicon of ASL. After all, there already IS a sign for hamburger.

How does this relate to the Uncanny?

In a sort of cultural maskaphobia, the masked King character has in recent history become a pop icon that has been aligned with the uncanny quite often (Adam Kostko, for instance, features King as his primary and defining icon of the book Creepiness in mass culture — this great excerpt in the journal, New Inquiry is well worth reading fully). Like many “dolls which come to life” in the literature and film of the uncanny, the commercials for King are always inherently uncanny because his unrealistic mask refuses access to the identity of the person miming behind it, causing us to suspect some “unseen force” — a strangely inhuman-yet-humanlike agency — is at work here with a mind all its own. The “Wake up with the King” TV commercial campaign has been treated as emblematic of this creepiness.

As I frequently have argued, cartoony advertising spokesmodels and mascots (think of animated figures like the Pillsbury Doughboy or Michelin Man) often attempt to embody a corporate entity — a business — as if it were a singular life all its own. This is, actually, what a “corporation” is: an embodiment of an idea. Along the way, repressed desires and secret wishes are “released” or affirmed publicly by them, rendering these dolls a sort of living-dead commodity fetish.

While the “Wake Up” ad literally is a dramatization of “breakfast in bed” served up by a corporate mascot, Kostko reads this commercial as rife with homoerotic tension, triggering a “return of the repressed” sensation, and that clearly is evident in this bedroom scene. From the dominating intimacy of the King lying “in bed” with the consumer to the comedic moment where they hold hands across the man’s knee, the sexual innuendos are everywhere in evidence, displaced onto the closeups on the sandwich as if this fetishism were the consummation of pleasure. Add to the mix a very obvious, yet easy-to-overlook element of social class issues: the topsy-turviness of having a clownish representation of royalty “serve” the common, working class man. What is uncanny about this is not merely (or only) a “return of repressed” sexual desire, but a kind of economic wish-fulfillment as well — a comedic inversion of social roles, implied by the King’s chummy servitude, where a man can be served breakfast in bed by a representative of elite economic power, who in turn is a capitalistic icon of consumer culture. Fitting, then, that it is a food object that is fetishized here as if it were not just sexual, but supernatural. The sandwich is a “double croissandwich” — described in voice over and in replay where the phrase “egg and meat and cheese” is repeated. In other words, we have an uncanny doubling.

In hindsight, looking back at this ad through the context of this week’s campaign in which the King “breaks his silence” through hand sign — it is worth paying attention to how sound actually functions in the “Wake Up with the King” advert. There is birdsong playing as ambient sound while the man in bed is shown sleeping, and we probably don’t even recognize in the background that the King’s regalia is there behind his head, subtly moving with King’s breathing. The “creepy” King is performing something voyeuristic here right from the onset. But if we are situated with the viewpoint of the sleeping man, then the advert begins in a dream state. The man in bed awakens to the shock of reality-as-dream: the fantastic King towering above him.

There is the momentary beat of shock and wonder — what is this creep doing in my bed? what are his intentions? — when the King gently raises his finger in a “hold on, let me show you my croissandwich and explain” sort of gesture. The score plays an uptempo song for the remainder of the ad, characterizing his intent as safe and fun-loving, echoed by the somewhat gravelly and strange voice-over (one we might inherently assign to the King himself by association). But what is interesting to me is that the King DID use hand signals in this early commercial: he always has relied on pantomime; he always already has been gestural.

But the new “whoppersign” campaign has its own uncanny appeal, as it brings together bodies with language through sign language. And there is a strangeness to all this that I would speculate is felt as uniquely uncanny most of all by the deaf consumer, since their special needs are usually ignored by advertising and brand marketing (beyond minimal tokens and expressions guided by the basic legalities)…yet here they suddenly, surprisingly, are spoken to visually by someone who doesn’t speak at all to the typical hearing-abled consumer. This reversal of roles could be experienced like a “secret language” come to life in the public, by the mass market.

When the King was silent, as he mostly has been up to this point, he’s chilled us with paranoid concern about what that king-thing might be thing-king. No longer do we worry what’s on his mind; we don’t attribute suspicious motives to it, since it finally is speaking to us, and it “comes to life” in a new way that is human. The hands divert our attention… they are “real” albeit disembodied (and perhaps oddly thin, long and pale), as they are detached from a “head.” Yet we “know” this is a human in a costume, someone capable of composing and signing language with a mind. When King starts to “speak” with its hands, you may at first feel a sensation of the uncanny, but the longer it “speaks” — and the more we witness it (him?) interacting with others — the safer and more domesticated King becomes. His intentions, implicitly, are pure. The King is not an evil embodiment of weirdness. The suggestion is that he has been a special needs monarch all along. (This would suggest that his Otherness is really a construct of fears by the normative masses all along, too — the masses who, it should come as no surprise, have a long history of representing and often demonizing the disabled as Other. This “ableist Othering” treats people with unfortunate disabilities as abnormal, monstrous, alien or supernatural — something lesser than a socially-normative construct of the Self.)

Is the Uncanniness of the King spokesmodel being culturally turned around to progressive ends? Perhaps, so long as the King and the corporation alike respect the marginalized “voice.”

All things considered, I think the must “uncanny” sensation that this campaign unleashes is located in the nature of the sign itself. Freud has famously written that the uncanny is launched “when the distinction between imagination and reality is effaced, as when something that we have hitherto regarded as imaginary appears before us in reality, or when a symbol takes over the full functions of the thing it symbolizes.” This is precisely what we see when the Burger King sign, logo, and even menu is rewritten in ASL — returned to us language that is “the same” yet “unfamiliar” to the everyday consumer.

And it is doubly estranged to the deaf themselves, who do emotionally-loaded double-takes when they first encounter signs of hand expressions where there “should be” lettering, signs where there once was logo, signs substituting for signs. The uncanny triggers a gasp of pleasure or amazement — as the company breaks through the monolithic presumption of English print language in the form of ASL’s direct address.

It is important that this whoppersign be constructed by the community they are speaking “to.” ASL isn’t written by any one entity just like Webster did not invent the English language. Instead, French sign language was adapted into English and standards emerged in schools for the deaf. The whoppersign, albeit corporate branding, is asking the deaf to create a sign — a phoneme of language — that does not exist, to symbolize their brand of hamburger. That is passing the power of advertising over to the people; it is active culture empowerment, acknowledging and giving “voice” to a segment of the population that is often ignored by mass marketing and literally silenced by the culture, who chooses not to listen. At the same time, it is corporate branding of graphic language in the interest of revising a cultural story about their King icon — reframing his silence as not creepy or uncanny, but merely misunderstood and marginalized.

Whoppersign is not yet settled. There is no “winner” yet, selected by the corporation. I think it is up to the hearing-impaired community to adopt these expressions and conventionalize them. But for now we have an advertising brand name rendered a living, moving entity — a symbol-under-revision — a structure deconstructing in the linguistic system of the popular uncanny. There are many issues with profiteering off the marginalized, too. But what what we seem to have right now is a kind of performance of consumerism, via viral video marketing, as a pantomime of empowerment.